Investing in Lasting Values

Last December, culture360 launched a series articles on how the arts are adapting to the "New Normal". Well over 10 months into the global pandemic, this series will present experiences and stories of resilience, adaptation, and success from the arts sector to the Covid-19 pandemic, with particular focus on differently disabled artists and arts organisations, artists residencies and arts funding.

A scrutiny of Italian and Norwegian art markets reveals that, contrary to popular beliefs, the art market in many cases fares better than before the pandemic. Events-based activities, however, suffer. In spite of major differences between the two countries’ artistic traditions, patrimony and state subsidies, the Norwegian and Italian art markets have reacted in a remarkably similar way to the pandemic.

Peaking sales

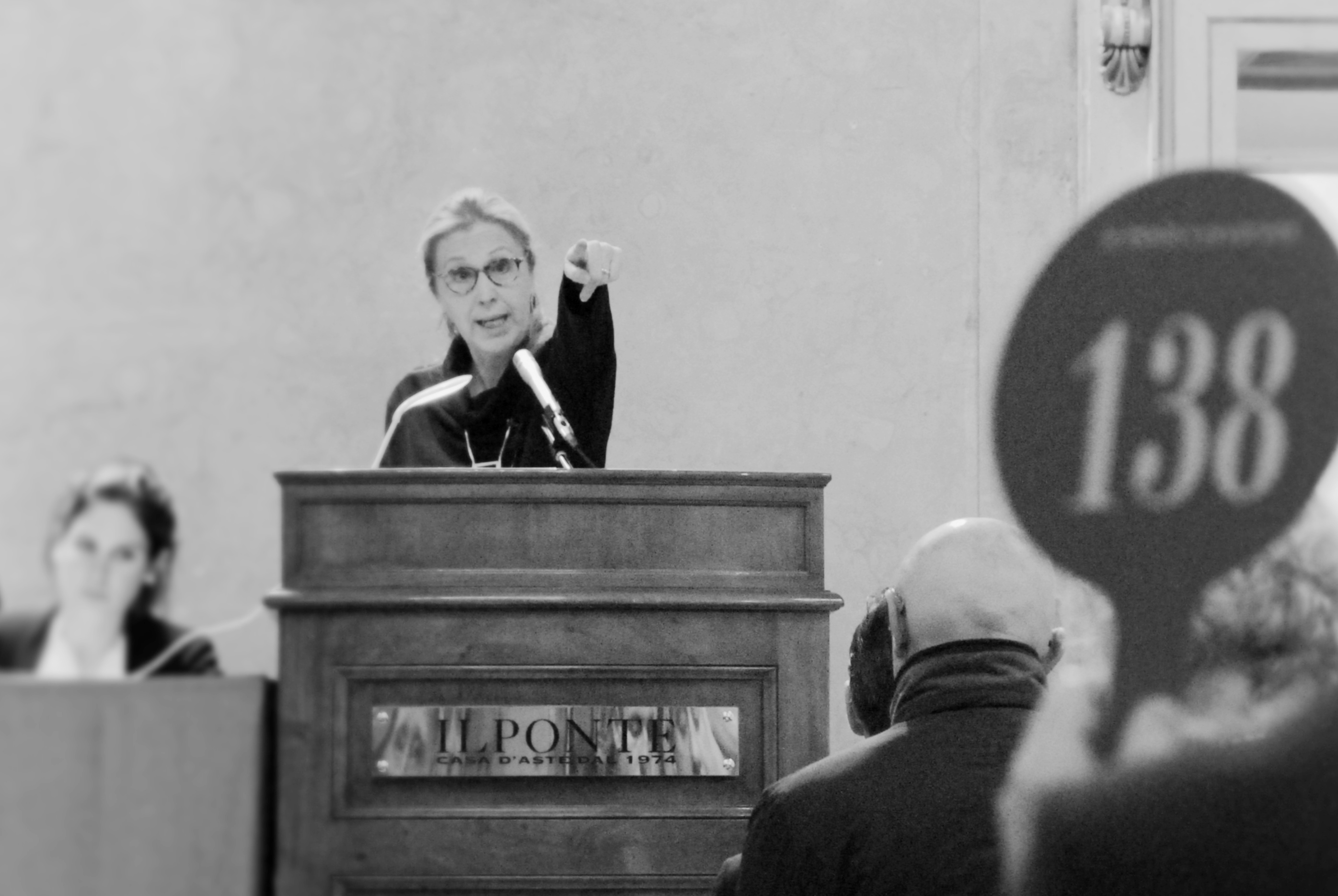

"The pandemic caused us to make major adjustments to how we operate, from how we inspect and collect pieces for sale, to how we organise the actual auctions. But the reaction from the audience has been overwhelming", says Rosella Novarini, Director at the Ponte Casa d’Aste in Milan. "We’ve sold some 75% of the items on sale, with a peak at 96%. In some auctions, the revaluation of the items on sale have reached 200% of the initial estimate."

Il Ponte is not alone; similar experiences have been shared by Norwegian auction houses.

"Our traditional autumn auction was our best ever, states Pascal Nyborg at the Christiania Auksjoner in Oslo. We hoped to sell for 13 million kroner but we recorded a total of 20 million at closing. One painting, a Ludvig Karsten piece from 1914, was estimated at 1,5-2 million but sold at 6,2 million kroner," Nyborg explains.

Pascal Nyborg, Christiania Auksjoner

Hans Richard Elgheim at the Grev Wedels Plass Auksjoner, another prominent auction house in Oslo has had a similar experience. They were considering postponing the first auctions after the lockdown, but fortunately they didn’t; they’ve sold more expensive paintings this year than last year.

Both Nyborg and Elgheim believe that the lockdown has made people focus more on their houses, their living space, and that the impossibility to travel has availed more money to spend on art. Nyborg also thinks that volatile stock markets have made art a more desirable investment.

"People invest in lasting values," he points out.

Modern and contemporary art, young buyers and online bidding

Rossella Novarini at an auction. Photo: Il Ponte Casa d'Aste

To attract younger buyers, both Italian and Norwegian auction houses have changed their selection, focusing more on modern and contemporary art, and they have also revamped their systems to allow for online viewing and bidding. That opens up completely new markets and allows for potential buyers to bid at various auctions in different countries from their home, a major development with positive effects on sales.

The possibility for online bidding has for many opened the door to an entirely new way of buying art. According to Rosella Novarini, they’ve experienced the thrill and adrenaline of a bidding process; a unique experience that for many people becomes hard to give up.

Stefano Andrea Poli, who is responsible for 20th C. decorative art and design at the Ponte, suggests that Italian auction houses might have an advantage in this new, online global art market because of the vast Italian artistic patrimony.

Public funding used to push online activity

If Italy has an advantage in terms of availability of art, the Norway art sector benefits from another perhaps no less important advantage in the era of the pandemic: availability of public funding. It is difficult to get an overview of just how much the Norwegian state has supported the cultural sector during the pandemic because the support is spread across different initiatives, ranging from an immediate ‘corona-stipend’ to a compensation fund and a stimulation package for the cultural sector. Only the latter two amount to no less than 900 million NOK (almost 85,7 mill euros), and come in addition to the initial 70 million NOK (6,6 million euros) provided to artists during the summer.

Both artists, exhibition venues and galleries have been able to apply for funding on the basis of specific projects. One of those that did receive funding is Christian Hanno at the online Atelier Open, an online gallery set up to be a bridge between potential buyers and artists that are not represented by a traditional gallery.

Atelier Open has received public funding to finalise an art-subscription arrangement, whereby potential buyers that find a piece of art they’re interested in on Atelier Open’s webpage, can rent that piece for some time before they decide to keep it or give it back.

"The state support has made it possible for us to finalise this project much earlier," says Hanno. "The new system is probably one of the reasons that Hanno report of positive results in the wake of the pandemic. We’ve increased both our revenue and the number of artists that use us as an intermediary. Probably we’ve also benefitted from the cancellation of festivals and fairs that many artists depend on to make their art known."

Italian galleries not considered a business?

In Italy on the other side, state funding has been routed differently, targeting different actors. The Italian Ministry of Culture and Tourism, MiBACT, has provided 9 billion euros, divided, however, between the culture and tourism sectors. If counting only the cultural sector, public support in Italy amounts to some 2,6 billion euros.

As opposed to in Norway, where arrangements allowed for small and medium-sized institutions as well as individual artists to seek funding, the Italian support priorities large, often public institutions.

Most private gallerists in Rome who operate on a partita IVA – a single person business structure common in Italy, had the right to 600 euros in state aid during lockdown, but did not have access to funding to support their businesses as such.

"I managed well during the pandemic, but I did it on my own, without any public support," says Maria Laura Pirelli, owner of the Galleria Thripè, a small, private gallery in Rome’s Prati neighbourhood. Pirelli shares that she chose a new and upcoming artist for her first exhibition after Italy reopened, and that she purposely prolonged the duration of the exhibition. Both affluence and sales have been at pair with the pre-pandemic situation.

Other galleries, especially those heavily reliant on tourism for affluence and sales, struggled more.

Interestingly, the vast Italian artistic patrimony that is an ace up the sleeve for Italian auction houses, might reflect negatively on smaller galleries. According to Pirelli, the lack of targeted state support to the gallery sector, might be because the Italian state doesn’t see this sector as business that can benefit the Italian economy. "We should use this situation to reflect on how to change how people look at private galleries in Italy," she says.

Arts is a spatial experience

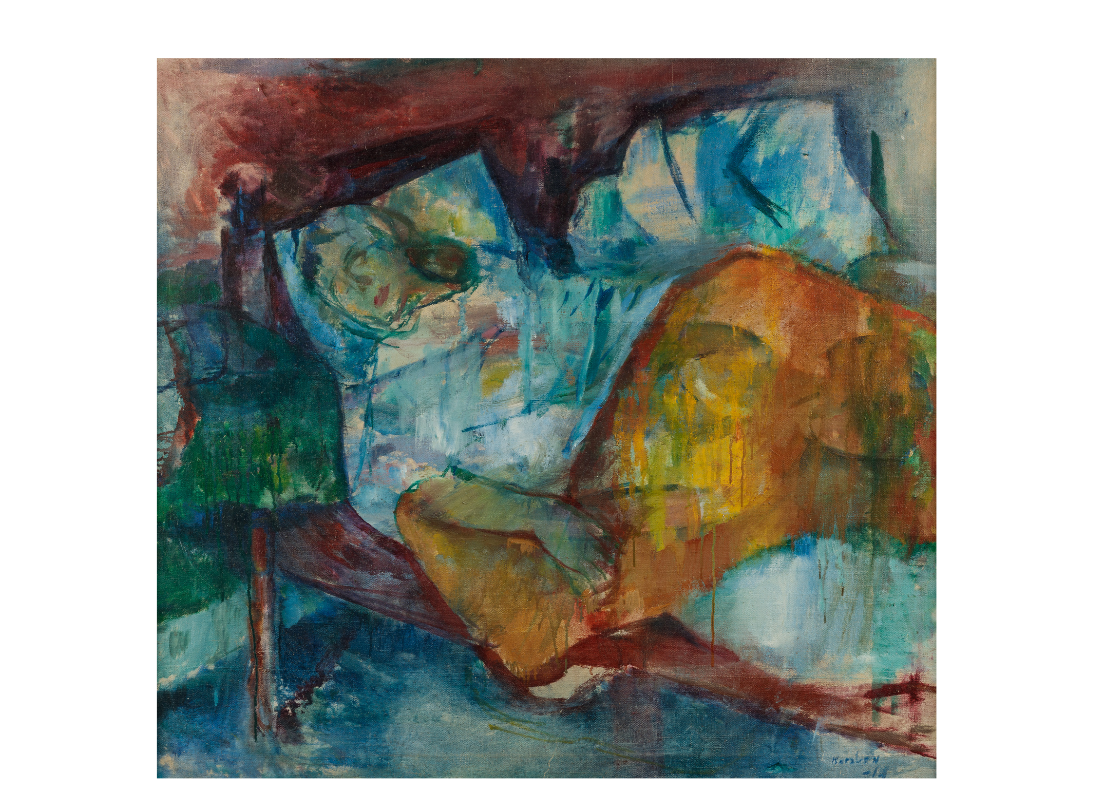

Ludvig Karsten painting that sold at 6,2 million NOK - Courtesy Christiana Auksjoner

The public funding may have helped many Norwegian art operators overcome a difficult period, but the public funding came with some caveats. For artistic production and organisers of art events, the project based funding largely meant putting on hold ongoing work in favour of new pandemic-induced projects which often translated into online experiences.

In Bergen in Western Norway, the artistic group and exhibition centre Alt Går Bra, saw their lives and professional plans change radically because of the pandemic. Out of 76 events planned for this year, 21 were cancelled because of the pandemic. Of the 55 events that actually took place, 16 were moved online.

Alt Går Bra received 150 000 NOK (app. 14 000 euros) in state support, but their representatives explain that the support had to be used for new initiatives related to the corona situation, and that ongoing projects had to be put on hold. – We could not use the money for recurring costs, they say, – the government did not seem to have a lot of understanding of how costly it is to run an artistic practice. At Alt Går Bra, it seems they’ve tried to adapt to the demands of digitalisation and ‘corona-friendly’ events, but they feel that the change is not exclusively positive.

"It’s not easy to substitute personal encounters in the art field," says Agnes Nedregård, one of their representatives. "Visual arts in particular is a spatial experience that can’t easily be replaced by the internet."

Main image: Hanging pictures at Alt Går Bra. Photo: Eva S. Johansen, Nordnesrepublikken

Eva-Kristin U. Pedersen (39) is a Norwegian journalist based in Rome. She writes regularly for the Norwegian press about Italian and European politics and society, humanitarian aid and development and, as often as possible, about art. She has also contributed to the organisational aspects of several art exhibitions and related events in Rome.

Similar content

posted on

28 May 2011

posted on

30 Nov 2012

from - to

14 Oct 2020 - 18 Oct 2020

posted on

06 Sep 2010