Media Piracy in India

Piracy in the Media and Entertainment Industry

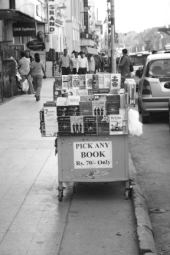

Piracy in the Media and Entertainment IndustryWalking down the chaotic west end of the Mahatma Gandhi Road in Bangalore, a popular hub in the Information Technology city of India, the small racks selling pirated copies of the latest Hollywood, Bollywood and Tamil films could almost go unnoticed. The air is filled with exhaust fumes of Auto Rickshaws wading through the cluttered traffic on the street where besides the vendor is an upcoming metro rail, retail stores, tea vendors, food stalls, cigarette corners, banks, pubs, shopping plazas, a bustling urban India, connected through formal and informal networks of technology.

Construction laborers, shoppers, young IT professionals and the odd passerby alike, huddle around the pirate rack, set up a few inches above the ground. They flip through copies of the latest releases displayed by the street vendor. While one DVD stores up to three films, many are especially selected collections, based on genres, directors, actors etc. The vendor quotes a fixed price of Rs.60 (approx. 1.50 USD) but the bulk consumer can expect a healthy discount. Ask for the local Kannada films and the young vendor quips, “No Kannada boss! The police will shut our business if we are found selling those.”

The introduction of color television and VCR technology during 1980’s marked the beginning of the copy culture in India, taking celluloid from the public and mass audience cinema halls to private living rooms. The decade of the 1990’s was lived on the cusp of legality and illegality - first with the proliferation of cable television networks and later with the introduction of the VCD technology in the later half of the century. In the past ten years the evolution of newer digital and internet technologies, combined with the effects of market capitalism have created a thriving environment for creation, aggregation and distribution of content, products and services, news and information, advertising and entertainment through various channels and platforms. The media and entertainment industry in India is forecasted to grow at an annual rate of 19 percent to reach Rs. 83,740 Crores (18.6 Billion USD) by 2010. As the fastest growing media industry in the world, it has also generated considerable debate around piracy, especially when it is perceived to be eating the industry’s profits.

Video: What do you think of media piracy?

Media Windowing and Pirate Circuits

Cinema audiences in Bangalore visiting movie theaters are offered movie ticket prices ranging from Rs.60 (approx. 1.50 USD) to Rs. 500 (approx. 11.40 USD) for a show, depending on the choice of their theater, timings of the show and the other peripheral services that the cinema hall would offer. The time of release of the VCD or DVD is decided by the popularity of the film. The time frame has traditionally ranged between 2-6 weeks after the release of the film. This is also the time that the film becomes available across rental stores. The ‘Direct To Home’ or ‘Pay per View’ rights are also released a few weeks later, based on the popularity of the film. The smooth functioning of this sequence is critical for media companies to recover their costs and gather their profits. Film producers describe a film as a "block of ice" which is melting in their hands, and unless they can quickly make their money, through a planned release, they run the risk of having the block of ice melt away and turn to water! Even as the film is released, the pirated copy of the same film becomes available in the ‘grey’ market within 1-2 days, at a price one tenth of the original. Duplication of content in the digital medium enables pirates to disrupt the chain of maximizing profits for distributors. While the costs of reproducing every duplicate copy constantly decreases, the quality of the content remains constant with each generation of duplication.

Moser Baer - Fighting back the Pirates

In formal markets, optical discs are sold through vendors at local video and audio shops located in residential areas, specialty chain stores exclusively selling films and music (such as Planet M), bookstores (such as the Crossword chain) and shopping malls (such as Reliance Time Out). The location of the store and the type of consumer decides the type of content on sale. While up market retail stores sell English, Hindi and Regional Content from across the country, there is a higher chance that the small shop by the street only has popular Hindi and local content.

The pirates had been controlling almost all of the home video market in India, until Moser Baer, the world’s second largest manufacturer of optical storage media like CDs and DVDs, took a cue from the pirates business and jumped into the entertainment industry in 2007. The distribution of films in India has seen a revolutionary shift since Moser Baer’s rise in the film market. With unique distribution strategies, one can even buy discs at the closest grocery store.

The company started by picking up home video distribution rights to over 10,000 films from small distributors who were willing to give away these films at a small price. In the past two years, the company has released 60 percent of these films. After a favorable response by consumers who rapidly picked up discs of old releases, with the starting price of Rs. 34 (less than 1 USD), in 2008, the company stated collaborating for new releases. In a deal worth Rs.250 million, it acquired home video release rights to UTV's home video catalog which included 10 films. It also has the rights to films under production films until mid-2009.

According to Sanjeev Varma, Head of Corporate Communications at Moser Baer, the “Name of the Game is Speed”. He exemplifies 'Jab We Met', a popular Bollywood film which sold over 6 million copies on Home Video after it was put out in the market by the company five weeks after its release. Before Moser Baer entered the entertainment industry, the window between a film’s release in the cinema and home video release was over 3 months. This huge time lag, easy availability of the film in the informal market even before the release of the film and non competitive prices ensured that the pirates were in control of this segment. In the past two years, Moser Baer has been able to wean away a 10 percent share of this market with the help of competitive pricing, aggressive marketing and urging customers to “Kill Piracy”.

Torrent Trends – The new face of piracy

Shift to a cybercafé outside Christ College in the city, where a bunch of youngsters are busy playing the latest PC game Sims 3 World Adventures. It is no surprise that they have downloaded the film online, using a Bit Torrent client. When you enquire about the legality of downloading, the young boys retort, “How else do you think we can access these games? Sims 3 would not be released in India for another six months, and when it does, it would be completely unaffordable for us to buy an original. Everyone downloads!”

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file sharing protocol used for distributing large amounts of data. It has been controversial since its inception, earlier with the Kaaza and Limewire lawsuits and more recently, the pirate bay trial.

In India, BitTorrent is coming of age, especially for the urban youth, who access content such as films, music and software from around the world, at the click of a mouse. The Bit Torrent news site Torrent Freak reported in 2008 a tripling of Indian visits to Mininova—a large international Bit Torrent site—over the previous year, and the recent appearance of India in the top ten traffic sources for most torrent sites. Torrent sites occupy three of the top 100 visited sites in India according to Alexa, a web rankings company. International torrent sites, for their part, have developed extensive collections of Indian media, including especially Bollywood films.

The PC penetration in India is still low at 30 computers per 1000 people – roughly a quarter of China, whereas according to the Department of Telecommunications, broadband Internet services have reached 6.2 million subscribers in 2009. However, the comparatively slow overall progress of PC and Broadband deployment disguise the impact of Internet access in the urban Indian landscape. According to a survey in 2009 by Manufacturers Association for Information Technology (MAIT), internet penetration in the top four metropolitan cities is over 25 percent. The growth of broadband connectivity is set to change the pirate practices in a significant way. The niche market of pirates is fast diminishing. At the biggest wholesale pirate market of Bangalore, a dealer retorts, “Earlier we used to keep special collections of world cinema because the customers demanded it. Now they are fast migrating to Internet and File Sharing. Our business is now one-third of what it used to be three years ago.”

Anti-Piracy Enforcement and Literature

The public discourse on media piracy has largely been created by media companies and anti-piracy groups leveraging on their ability to lobby for changes in laws and stricter enforcement. The struggle to impose new forms of property regimes finds itself at loggerhead with increasingly cheaper technologies for circulation of media commodities. Motion Pictures Association (MPA) has been the most active institution in creating rapid action against film piracy in India. The India wing of the Business Software Alliance (BSA) has been a key agent in creating information on software piracy and assisting the police in conducting raids on pirates around the country. Apart from these groups, the Social Services Wing in Bombay, The Indian Music Industry (IMI) and other major producers such as Reliance Entertainment, Anil Dhirubhai Ambani group, Ramesh Sippy, Yash Chopra, Mukesh Bhatt, Sharukh Khan, Amir Khan, and distributors such as Ronnie Screwwalla of United Television and Eros International have driven anti-piracy efforts within the film industry, through associations and coalitions, formed with a push by the MPA. These groups have recruited ex-police officers such as Julio Ribeiro and A.A. Khan to identify pirates and assist the police in conducting raids in various parts of the country.

Apart from enforcement efforts, anti-piracy lobbies, such as the MPA, IMI, BSA and USIBC have also been instrumental in creating literature and annual statistical publications to demonstrate the losses caused by piracy. Since 2004, these reports have been commissioned to an assortment of consultancy firms, including Price Waterhouse Coopers, KPMG, Ernst and Young and IDC, which have published piracy estimates, usually based on the International Intellectual Property Alliance.

These figures and estimates have displayed a tendency to induce a feeling of “shock and awe”. For example, an article published in Mint, a leading financial daily reports, “Piracy and counterfeiting are growing and deprived the Indian entertainment industry of some $4 billion (Rs16, 240 Crore), or almost 40% of potential annual revenues, as well as around 820,000 job.” Similar reports have accounted for piracy figures based on reports such as the above stated USIBC-E&Y or similar statistics published and released at gala media events.

There is a lack of critical questioning of these reports by the media, despite enough scholarly research pointing out the flaws in these statistics. Most of these accounts are quantitative in nature and do not describe the social class or demographic break up of those who engage in piracy or buy pirated products. In other words, they flatten out issues of social or economic difference in their picture of the phenomenon, and do not prompt a deeper reflection on issues such as endemic unemployment, affordability and access to culture.

Relevant links

www.sarai.net

http://cis-india.org/advocacy/ipr/blog/the-dark-fibre-files-steal-this-film-and-the-pirate-bay-trial

http://pad.ma/find?f=category&q=Copyright

Related culture360.org article: India: media piracy-intellectual property interview

Related video: What do you think of media piracy?

Siddharth Chadha is based in Bangalore and currently associated with a research project “Towards Détente in Media Piracy” with Alternate Law Forum and Sarai-CSDS. The project is supported by the International Development Research Centre, a Canadian Crown Corporation that works in close collaboration with researchers from the developing world in their search for the means to build healthier, more equitable, and more prosperous societies.

Similar content

posted on

04 Jan 2013

posted on

19 Mar 2014

posted on

12 Jun 2011

posted on

12 Jun 2011

By Siddharth

20 Nov 2009