The Situation and Directions of Philippine Independent Cinema

Last year, mainstream producers in the Philippines made only 28 films. Not only does this indicate a steep decline in the film output of mainstream cinema, this also gives a sharp contrast to the more than 100 independently produced films in the Philippines last year.

Last year, mainstream producers in the Philippines made only 28 films. Not only does this indicate a steep decline in the film output of mainstream cinema, this also gives a sharp contrast to the more than 100 independently produced films in the Philippines last year.To say that independent filmmaking has become the soul of Philippine cinema is no longer an exaggeration. For years, Filipino independent filmmakers like Kidlat Tahimik (Perfumed Nightmare, 1977), Raymond Red (Anino, 2001), and Brillante Mendoza (Kinatay, 2009) among many others have received critical acclaim worldwide. As film festivals, competitions and distribution channels such as Cinemalaya and Cinema One have motivated young maverick filmmakers in recent years, indie films have become synonymous to creative content and perspectives for many Filipinos today. Although the Philippine indie film industry has come a long way from its early developments in the Marcos era when realistic portrayal of Filipino society in the arts was not considered “beautiful” by the dictatorship, government support is still lacking to sufficiently help indie filmmakers.

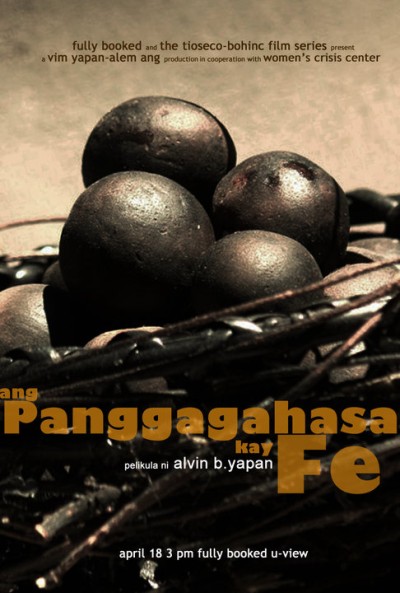

[caption id="attachment_2682" align="alignright" width="280" caption="Poster of "The Rapture of Fe" the first film of Alvin Yapan"]

Alvin Yapan, whose current project with Alemberg Ang, Ang Sayaw ng Dalawang Kaliwang Paa [The Dance of the Two Left Feet] is one of Cinemalaya’s selections for full length feature, says that Filipino filmmakers have the range of talent, they are inadequately supported especially when compared with other countries. Filmmakers have to seek partner institutions to underwrite productions costs. Advocacy films are usual since sponsors more easily patronize them. Although this is not necessarily bad, this limits the range of films produced.

Paul Sta. Ana, writer of Bisperas [Eve], one of Cinemalaya’s selections for the director’s showcase category, says that the government’s fund allocation for film reflects its mainstream filmmaking attitude. The government tends to spend millions of pesos, that would otherwise produce many indie films, for one film project.

Both filmmakers observe the fluid bounds between mainstream and independent cinema. Yapan says that this is currently most clearly shown in Cinemalaya’s Director’s Showcase for films by Filipino directors who have made at least three full-length commercial feature films. For Sta. Ana, there are indie filmmakers who also intend to go mainstream in the future.

In the end, what distinguishes independent cinema is its priority for artistic endeavor (over financial gain, vis-à-vis mainstream cinema) while still being accessible to the audience (vis-à-vis alternative experimental cinema). Each filmmaker attempts to show his own story in an original way.

There have been several issues on Philippine independent filmmaking that have become apparent especially after its emerge a few years ago. One of these is the prevalent theme of poverty that exoticizes, even exploits, Filipino poverty. Sta. Ana notes that the main issue here is the intention of the filmmaker which, he admits, is hard to determine. The question is whether filmmakers are producing these films because they want to reveal Filipino reality or they seek the attention of international film festivals. He says that context is crucial not only in conceptualizing and presenting the material of the film but also understanding the subject position of the filmmaker.

Yapan remarks that if current indie films are to be observed, one can predict that the themes will diversify. He says that the audience can expect new things to come out in the coming years far from the “poverty porn” (the term critics use) that indie films have been known for. For him, therefore, these issues have been settled; the more important concern now is distribution. Where the films are screened, given the lack of marketing tools that mainstream producers have and the strict film censorship restrictions in popular movie houses, is always a problem.

On December 16, 2010, the Philippine Daily Inquirer honored 25 independent filmmakers on the occasion of its 25th anniversary. Present in the event were Briccio Santos, the head of the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FCCP) and Mary Grace Poe-Llamanzares, chief of the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB). Both government agencies promised support to the independent film industry.

Llamanzares said in her speech that to establish a new board that is “fair, open-minded and responsible,” she made sure to include a representative from the independent filmmakers. Acknowledging the importance of the industry to national culture, she said that the government is looking into the possibility of exempting or reducing the tax charges of qualified indie films.

Santos, who is also an indie filmmaker, said that the FDCP is putting forward initiatives that will come to the aid of the filmmakers. One of these is the launching of “Sineng Pambansa” [National Cinema], will be first held from Jan. 19 to 21, 2011 at SM City Iloilo. Cinematheques or alternative screening venues will also be set up nationwide in cooperation with local government units. In 2011, cinematheues in the cities of Makati, Baguio, Cebu, Davao, Cagayan de Oro and Iloilo will be inaugurated, and will be eventually followed by the opening of screening venues in all 16 regions of the Philippines. The goal of the council is for independent films to be distributed to a wider audience.

If these assurances were to be believed, we can look forward to momentous developments in the Philippine independent cinema before long. For now, what we can hold on to is the vast collection of impressive Filipino independent films and the remarkable talent of Filipino independent filmmakers. They will continue making films, for creativity is not because of the material conditions at hand, but is even intensified because of, and despite of, the lack of them.

by Francis C. Sollano

Francis C. Sollano is an editorial associate of Kritika Kultura, an online, peer-reviewed journal of language, literary, and cultural studies, and a contributing editor of Titig, a magazine of social and cultural critique. He is an assistant instructor in Ateneo de Manila University, where he is also currently taking MA in Literary and Cultural Studies.

Similar content

from - to

15 Jul 2011 - 24 Jul 2011

By Kerrine Goh

29 Mar 2004

posted on

23 Sep 2018

posted on

16 Mar 2012