From Rural to Cyber: Representation of Women

At the recent Singapore International Film Festival, Mardhiah Osman caught three films that dealt with representation of the female gender.

The 17th Singapore International Film Festival 15 April – 1 May 2004 is yet another success, even with minor hiccups like cancelled screenings and change of venue. Thanks to the Asia Europe Foundation and the Singapore International Film Festival, I had the opportunity to catch 3 more films that has the common theme of female representation.

In a fictitious village of India where a baby girl born will not be greeted with glee, Matrubhoomi: A Nation Without Women, is one such film that is unapologetic in its delivery that will completely shock your senses. Contrary to the conventional mode of Indian filmmaking, this film is definitely not for the escapists who seek the traditional song-and-dance, and happy ending of Indian cinema.

Director, Manish Jha's presents a scenario where hefty female dowry impoverishment leads to infanticide. Matrubhoomi explores the severity of male destruction when the land becomes baron without any hope of a female nurturing figure. So, you would only hope that when they do come across a woman, that they would elevate her status to that of a goddess. No, that is not how the story developed as I had hoped because men are savages. After years of deprivation, they are reduced to barbarians, that of primal times. A group of men gather to watch a pornographic video and one resorts to releasing his energies on to a cow.

When the village priest stumbles upon, what might be the only girl in the entire village, he quickly reports this to a father of five sons who is willing to pay a huge dowry for his sons' marriage. And he does, and the girl is married off to not one but all 5 of the men in the family. On the wedding night, the father claims that it would only be fair if he gets to exercise conjugal rights! So takes place a most horrid experience for the virgin girl. Although Jha does not show any nudity on the screen, all acts of extremism of sex and violence are implied, just outside the frame. If you think by shutting your eyes during the film will save you from feeling nauseas, you are wrong. The musical arrangement is highly impactful in its delivery and warning to what is coming up. The girl is always visible but also always spoken for by the rest of the men around her.

The youngest brother falls in love with the girl, and resentment begin seeding within the other brothers to the point of the eldest brother murdering the youngest. The brutality does not stop there for when the servant boy tries to help the girl to escape, the other 4 unmercifully gun him down. The only two characters that show love and kindness towards her, face death at the hands of the other brothers. Obviously the deaths are legitimate to them because the acts of kindness are seen as threats to their continuing abuse of the girl. What is left to take place is a village coup among the family and the lower caste system that the servant boy belongs to. When the family imprisons the girl to the cowshed, without their knowledge, the entire village goes in night after night to rape her. The abuse escalates and the story just stops in development till the final massacre brought about by the entire village claiming paternity to the unborn child that brings the film to an end.

I am, though, a little disappointed at how the story does not explore the more emotional issues of the extinction of women, i.e., of nurturing, caring, and even issues involving the obvious, of men loving men. Instead, this was a narrative that explored hugely sexual deprivation and its consequences. With a title like A Nation without Women – there were endless possibilities of investigating what might and could have happened. Unfortunately, viewers are presented with what might take place, in a seemingly male prison.

Chu Yuan's Lust for Love of a Chinese Courtesan was made in 1984 but feels more like a 1960's classic. Happy Valley, a high-class brothel in ancient China is the premise of this film and its female lead, Chun, runs it, catering to the very elite male clientele of the village. Business is good mainly because the beautiful women of Happy Valley keep the affluent male customers entertained and serviced in the night. When there is trouble in the brothel, the mysterious swordsman, Hsiao Yeh who lives just outside Happy Valley, sorts its out.

While this is an erotic film first and martial arts film second, it also attempts, in my opinion at putting women in ancient China onto a higher status, of taking charge of their lives. Although a notable attempt, director Chu Yuan fails at this, as his main lead is defeated by her own creation, Ai-Nu. Also, Chun is a slave to her own desires of being rich and escaping the ordinary life by compromising her moralistic values. Chun is offering the girls a new life by taking them away from their poverty. To her, she is doing all of them a favour by feeding and clothing them

Ai-Nu, the peasant girl is kidnapped and forced into prostitution at the Happy Valley. She arrives bare with nothing. At first Ai-Nu rebels against her new fate but Chun who is reminded of her past in the younger girl, takes Ai-Nu as her prodigy. The two women share several very intimate moments of what is believed to be lesbian sex, and a confused Hsiao Yeh whom Chun also sleeps with as a reward for killing her enemies witnesses this. Similar to Matrubhoomi, sex is never shown but implied. However, the sex scenes in this film, are almost very clumsy and corny resulting in several laughter within the theatre. I am unsure if this was intended by the director, or simply just a result of a time and spatial gap between film and present audience.

This film though is not about lesbian love, as some audience would have anticipated or hoped. However, Lust for Love , is a story about betrayal to the self, how when one begins to compromise on the value system that you will embark in a one-way journey that will change the individual beyond recognition, as Chun did, and is finally defeated at her own game. Chun, the woman with obvious power that a moment of Achilles heel emotion destroys her. It is as if they story punishes women for having a dream.

When J. G. Ballard (author of Crash & Empire of the Sun ) predicted during a 1974 interview that “Sex times technology equals the future”, he already had some inclination that the computer interface will be the premise for most of our human activities. This discourse is recited in Webdiva.

Joanna, an 18-year old Filipino-American girl is forced to go home to the Philippines only to find her options limited. She turns to the world of cyber pornography and in time does very well for herself. Here is a girl who takes charge of her sexuality and exploits it to her gain. The film's guerilla-style camera maneuvers seem very awkward at times, as viewers are held up in both positions of the third person or the characters in the film itself.

When Jo finds love in the most improbable spaces (yes, you guessed it –the cyber arena), nothing is quite what it seems as her pornographic chat site is about to be clamped down by the authorities through her cyber lover boy and hacker, Spike. While there is plenty sex within the film's 105 minutes, Webdiva also tackles the omnipresent yet evidently undercover issues of the cyber sex trade and the Asian cyber revolution of the 21 st century.

While I am a little apprehensive about the inclusion of unnecessary sex scenes presented in the film that makes Webdiva feel like soft porn, the film does deal with postmodern problems of instant sexual gratification through virtual sex chats. Jo indulges in having an relationship with her online client of the pornographic website, Spike. Little is she aware that he is working for the police. This is yet another thread to the theme of women being manipulated and victimized. In a split screen sequence, Spike and Jo are visible on our film screen; however, it is only the male client that can see Jo, the Webdiva . Throughout their communication, Jo has no idea what he looks like. It is only at the end that they meet, when Spike bails her own out jail.

There are many upcoming female directors that share their story of being female, however, these 3 films are stories about women told by men. And although the male perspective is a valid one, the female voice needs also be heard. Perhaps, next time. Here's looking forward to the 18 th Singapore International Film Festival.

by Mardhiah Osman, a freelance writer based in Singapore.

Similar content

By Soe Yu Nwe and Nayoung Jeong

25 Nov 2020

from - to

23 Feb 2012 - 23 Feb 2012

posted on

15 Oct 2013

By Kerrine Goh

30 Apr 2004

By Kerrine Goh

25 Jun 2007

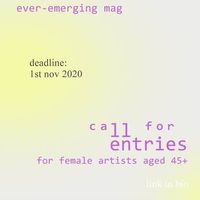

deadline

01 Nov 2020