Culture as an instrument – for better or worse?

In this article, Malaya del Rosario talks about how culture is increasingly being instrumentalised as a diplomatic tool. Should we be worried? Not necessarily. Read on to learn the different views around it, as well as practical tips to help artists and facilitators navigate the complex world of cross-cultural exchange.

As an art and culture manager, I have come to realise how challenging it is to balance artistic goals with stakeholders’ practical demands to achieve project success. Securing funding through grant proposals can be tough. It is not always easy to understand what funders really want. It is even harder when you are working across varied cultural contexts. And when you do manage to get that grant, there is always the challenge of balancing artistic goals with funder requirements. Add to that the importance of protecting artistic expression amidst unstable political environments.

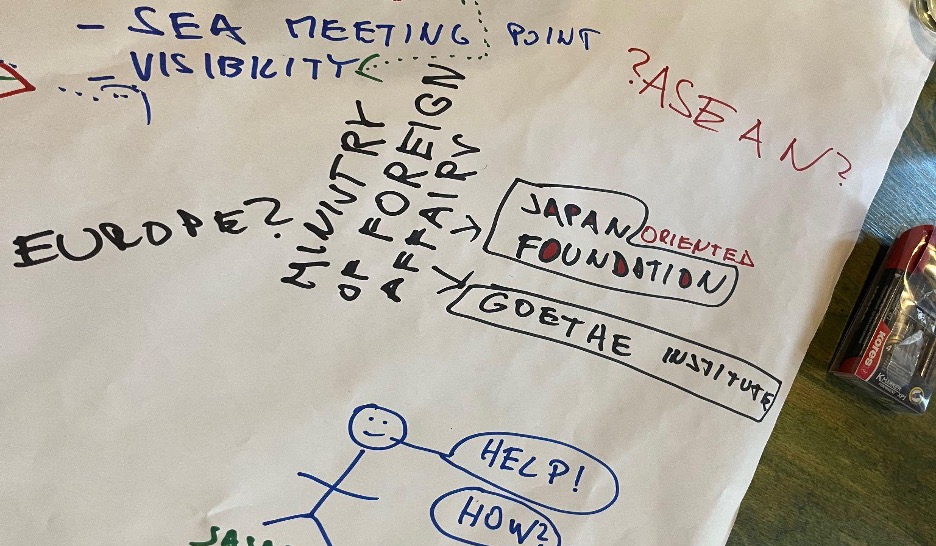

In May 2024, I had the privilege of joining ASEF LinkUp | Asia-Europe Cultural Diplomacy Lab in Prague, where, along with other experts and practitioners, we discussed the challenges of working in cross-cultural exchange. A key topic was how culture is increasingly being used as a diplomatic tool.

In this context, instrumentalisation refers to the integration of ‘culture’ as a concept in government and institutional plans to help achieve social, economic, or political objectives (Makarychev et al., 2020). It often serves predefined goals, such as fostering national identity, strengthening diplomatic relations, or more recently, achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Culture is tricky to instrumentalise due to its many interpretations. When defined as ‘the values, practices, and norms of a group’, it is often used for peacebuilding or social cohesion. ‘The arts’, on the other hand, are often attributed to supporting artistic work and creative expression. In the Nordics, for example, programmes on migrant integration involve artists for their ability to inspire and engage communities. Meanwhile, other initiatives can serve populist views on traditionalism and nativism, with art at risk of being used as propaganda (Ibid). When culture is intertwined with other agendas, a project’s original intent can be redirected or diluted. Being aware of these nuances will allow us to contribute meaningfully to diplomacy through the unique lens of art and culture.

How can cultural facilitators, whether they are art managers, cultural leaders, curators, or programme heads, navigate these complexities? How can we take advantage of opportunities while upholding artistic outcomes? Let us explore.

1. More than just for diplomats.

While some of my co-participants resisted the idea of instrumentalisation, others saw it as a way to connect their work with broader social outcomes. A key insight from the Lab is culture’s ability to create dialogue where political frameworks fall short. Our conversations reminded me of a 2015 interview I did with Patrick Flores, who curated the Philippine Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Featuring works by Jose Tence Ruiz, Manny Montelibano and Manuel Conde, it explored the complexities of neo-imperialism and territorial disputes surrounding the South China Sea. Flores, as curator, helped bridge the gap between national concerns and global issues on geopolitics. Nine years on, the exhibition continues to be a poignant reference for reflection and discussion.

Have you thought lately about the impact of your work in diplomacy? Are you highlighting this sufficiently in your project reports and evaluations?

2. Understanding layered agendas.

How can cultural facilitators navigate the layered agendas of funders and partners? Many grant programmes in the arts are funded by organisations with higher-level political or economic objectives. This is not necessarily a bad thing. On the contrary, understanding funder goals can help us align proposals with high-level agenda or broaden a project’s intended impact beyond the arts.

For example, the action plan to implement the ASEAN-United Kingdom Dialogue Partnership (2022-2026) aims to build regional cooperation, particularly, by addressing key issues such as the South China Sea dispute. While its primary focus is on trade and security, it also supports initiatives that contribute to wider diplomatic aims, and the arts sector stands to benefit from it. Organisations, like the British Council, utilise this framework to amplify their art programmes.

Another case in point is Japan Foundation’s government-funded, Asia Center, which was established in the lead up to the 2020/21 Tokyo Olympics. The programme facilitated exchanges in Southeast Asia and engaged over five million people through art collaborations. While it was designed to support state objectives, it also provided a platform for artistic production and sector development.

Cultural facilitators need to look into funding and governance structures to ensure that higher-level goals do not overshadow artistic outcomes. As Justin O'Connor argues in Culture is Not an Industry, reducing culture to a mere tool for economic or political gain can diminish its primary role as a common good.

Have you recently had to compromise following a funder request? How did it make you feel, and how did this impact your project outcome?

3. Protect the artists.

Funding bodies have the power to decide which initiatives are worth supporting, and, consequently, have a hand in defining which artistic practices are relevant and ‘of quality’. Some are flexible and allow artists space and freedom, while others require beneficiaries to shape their work according to predefined goals. Cultural facilitators, therefore, have an important role to protect the artists they work with from being censored, politicised, or misrepresented. Based on our discussions at the Lab, we can take proactive steps through:

- Transparency: Ensuring that artists understand the funders’ objectives and political context of the programmes they are part of. This allows them to make informed decisions about how to position their work.

- Advocacy for artistic integrity: Standing firm in ensuring that artists’ visions are not compromised. If a project leans too heavily toward a political agenda, facilitators can push for a more balanced approach that respects creative freedom.

- Contextual clarity: When presenting artists’ work, especially in international settings, it is essential to clearly communicate its context. This helps avoid any misrepresentation or exploitation.

Throughout these examples, there is a view that culture, when instrumentalised, becomes bigger than the arts. As cultural facilitators, we need to be aware of its fluidity and innovativeness to avoid stifling its vibrancy. However as we have seen, this is not a straightforward process. By recognising culture’s diplomatic potential, understanding funders’ layered agendas, and protecting artistic freedom, we can better navigate the complexities of cross-cultural work and its role in diplomacy. Ultimately, critical engagement will allow us to create more meaningful exchanges while keeping the unique value of art and culture at the heart of the conversation.

Further reading:

- Culture is Not an Industry: Reclaiming Art and Culture for the Common Good by Justin O'Connor (2022)

- Culture as an Instrument: Introduction to Issue 2/2020 by Andrey Makarychev, Miikka Pyykkönen, and Sakarias Sokka (2020)

- How Do We Navigate Cultural Diplomacy? New Report Launched (Asia-Europe Foundation, 2024)

- Worldmaking, New Empires, and Philippine Art: One on One with Patrick Flores by Malaya del Rosario (2015)

Cover Image: Notes from ASEF LinkUp | Asia-Europe Cultural Diplomacy Lab 2024. © Malaya del Rosario.

About the Author

Malaya is passionate about helping creative ecosystems thrive. She is an Arts and Creative Economy consultant, supporting cultural institutions and governments to amplify their impact through programme development, strategy building, research and content creation. She has been working in Asia and Europe for the past 15 years and has an MBA in Art and Cultural Management from the Institut d'études supérieures des arts and the Paris School of Business.

What do you want to see more of on ASEF Culture360? You can let us know until 31 October: fill in the survey here!