The Global Contemporary-Art Worlds After 1989 | A Summary of the Contemporary Art World?

[caption id="attachment_19036" align="aligncenter" width="602" caption="Raqs Media Collective, Escapement, 2009"]

[caption id="attachment_19036" align="aligncenter" width="602" caption="Raqs Media Collective, Escapement, 2009"]The exhibition The Global Contemporary – Art Worlds after 1989 was initiated by the Global Art and the Museum, a project by ZKM – Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. With more than hundred participating artists and a number of parallel events, this ambitious project is an attempt to show a compendium of contemporary art in a global context.

The words contemporary and the additional reference to the year of 1989 connects us inevitably with issues about time. In politics, 1989 was a year of transformations: the Berlin Wall fell and this event signed the end of the Cold War. The shape of Europe and the world changed. However, that year was also witness of the massacre of students in Tiananmen Square. For Germany, it was the year of its reunification, for China a slap in the face of democracy. Ironically, twenty two years later, the German government and the automobile company BMW supported the exhibition The Art of the Enlightenment, inaugurated in Beijing in April 2011 one day before Chinese artist Ai Weiwei was detained by police. Art has always been related to entertainment, power, the market and politics. But, what has changed in the global art world?

The question is why should we depart from a time frame if we talk about the global contemporary? As we know, globalisation is a quite old concept and it is not attached to the year 1989. In the title, the global is put in the same line as the terms art worlds, implying the existence of more than one and not the (global) art world. In this sense, the exhibition follows distinctions used during the landmark show Les Magiciens de la Terre, presented at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris in 1989, in which geographical descriptions of centre and periphery mattered. The difference here is the accentuation on the “now“ and the definition of contemporary. In the article Was bitte heißt “contemporary“?, curator and art historian Hans Belting says: “Globalisation is a power struggle for markets and consequently an obstacle for a coalescencing world. It has a double root in the modernisation and colonisation, but precisely for that reason the current appeal to live in a total present and contemporaneity is an attempt to release from these roots.”

But, can we actually escape from time and its multiple interpretations? A good example of this is the work Escapement (2009) by Raqs Media Collective. The installation with 27 clocks refers to various cities in different time zones, including fictional cities such as Macondo, Shangri La or the legendary Babylonia and indicating emotional states of being rather than giving information about time. A similar approach is the one given in the book The Invisible Cities of Italo Calvino, in which cities are associated to human desires. Additionally, a video with a young woman’s face and the sound of a heart beat reminds us of our human condition. No matter where we are, we might have similar emotions independently of our geographical or temporal location.

I want to be contemporary!

[caption id="attachment_19033" align="aligncenter" width="405" caption="Leila Pazooki, Moments of Glory, 2010"]

[/caption]

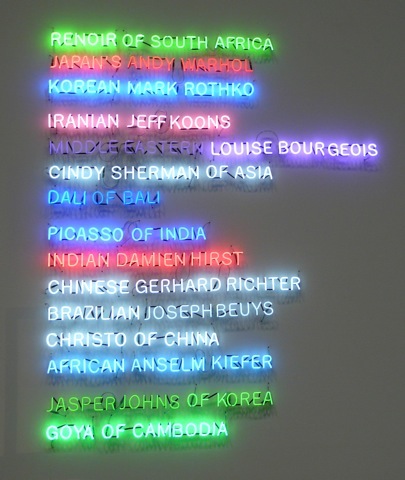

[/caption]Moments of Glory (2010) by Leila Pazooki parodies the art market by quoting phrases taken from online art magazines. So called ‘non-Western’ artists are compared with Euro-American icons of ‘Western’ art in colourful neon lights with the inscriptions ‘Indian Damien Hirst’, ‘Cindy Sherman of Asia’, ‘Dali of Bali’ or ‘Renoir of South Africa’. The work depicts the need of the market to use recognisable names in order to make an non Euro-American art scene visible. At the same time, these labels give us information about the quality of the works.

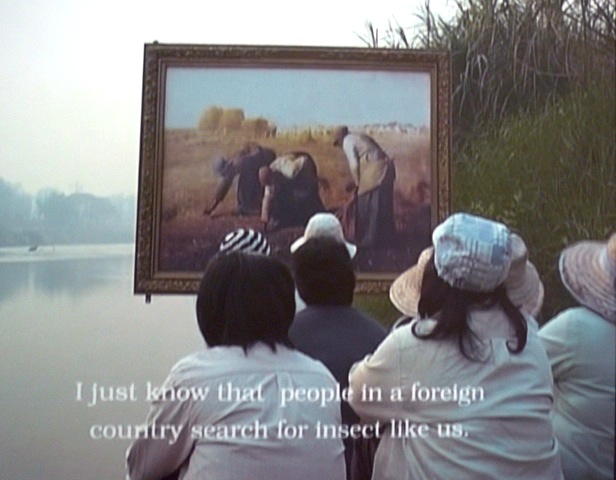

Topics such as the clash of cultures and opposing worlds are placarded in the work Dow Song Duang (The Two Planet Series), 2008 of Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook. In the video, a group of villagers in different rural locations in Thailand are watching masterpieces of 19th century landscape paintings of Jean-François Millet, Édouard Manet and Vincent van Gogh. With this, the artist gives an art illiterate audience the option to comment these works. Actually, if the take these artworks out of an art-related environment they will have different interpretations, not only in rural but also in urban areas.

[caption id="attachment_19034" align="aligncenter" width="616" caption="Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Dow Song Duang (The Two Planets Series), 2008"]

[/caption]

[/caption]In the essay The Future: Post-Cold War, Postmodernism, Postmarginalia (Playing with Slippery Lubricants) written in 1993, Thai curator Apinan Poshyananda stated: “Debates on marginalisation, postcolonialism, identity, minority and ‘otherness’ have produced much scholarly research and numerous exhibitions. However, too often workshops, conferences and shows related to these issues are confined to selected group of selectors. For instance, marginality is marginal to what? This invisible centre always seems to be somewhere else.“ By that time, he was already aware of the importance given to the texts about art and to art critics, and the initial central focus on curators (illustrated as ‘selected group of selectors’), influenced by similar academic readings. In some ways, the parallel programme Curating in Asia of the exhibition at ZKM echoed Apinan’s voice.

Yet, there is a strong focus on Asian artists, specially from Indonesia, showing works by Kuswidananto aka Jompet, Krisna Murti, Agung Kurniawan, Eko Nugroho, Tintin Wulia, and Jim Supangkat (who was invited as a curator and as an artist), and a lecture and screening programme about video art from Indonesia. But, it is a pity to see that the geographical reference of the global does not include many artists from Latin America or the Middle East. Maybe that was the task given to the curators of the Istanbul Biennale…

This is not a plastic bag

Accompanied by Buddhist chants, fifty students of the Luang Prabang School of Fine Arts in Laos travel in wooden motor boats along the Mekong River. Sitting in front of canvases, the students try to catch some impressions of the river landscape with their brushes. Once the boats approached a sacred Bodhi tree, some of the students all of a sudden jump into the river and swim in the direction of the tree. The poetical and thoughtful video installation of Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba The Ground, the Boat, and the Air: The Passing of the Bodhi Tree, 2007 is about a global human condition: we will always see the world in different ways, either contemplating the Bodhi tree or worshipping it.

[caption id="attachment_19035" align="aligncenter" width="630" caption="Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba, The Ground, the Root and the Air: The Passing of the Bodhi Tree, 2007"]

[/caption]

[/caption]Kader Attia’s installation Untitled (Plastic Bags), 2008-2011 shows literally nine colourful plastic bags on pedestals, that the artist collected from different parts of the world. Perhaps the piece alludes to environmental pollution? Though, the work is interpreted as a metaphor of the results of globalisation. In general, current global issues, such as natural disasters, religious struggles, poverty and revivals of nationalist movements are present in the exhibition merely as footnotes or comments.

During the inaugural discourses, all held in German (a global art language?), curator and artist Peter Weibel said that “since 1989, the world has shifted its view towards the East“. However, we would say that we live now in a global ‘westernised’ world, as capitalism, consumer culture, advertising and entertainment industry can be found most likely in any part of the world. Whether the attempt of summarising the global art world in one exhibition succeeded or not, it is interesting to see that the world did not change much in the last twenty years, in terms of human development and intercultural dialogue.

The Global Contemporary – Art Worlds After 1989

ZKM – Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe

Until February 5, 2012

References:

Hans Belting, Was bitte heißt “contemporary“?, published by Die Zeit , May 20, 2010

Apinan Poshyananda, The Future: Post-Cold War, Postmodernism, Postmarginalia (Playing with Slippery Lubricants), in: Turner, Caroline (ed.) (1993). Tradition and Change. Contemporary Art of Asia and the Pacific. Queensland: University of Queensland Press

Photo credits:

Raqs Media Collective, Escapement, 2009

Mixed-media installation, 27 clocks, high gloss aluminium with LED lights, 4 flat screen monitors, video and audio looped, dimensions variable (edition 2)

Photo: © Katerina Valdivia Bruch

Leila Pazooki, Moments of Glory, 2010

Neon light tubes, transformers, 15 pieces between 65 and 200 cm long

Photo: © Katerina Valdivia Bruch

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Dow Song Duang (The Two Planets Series), 2008

Video, colour, sound, 18:30 min.

Photo: © Katerina Valdivia Bruch

Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba, The Ground, the Root and the Air: The Passing of the Bodhi Tree, 2007

single channel video installation, HD, 14:30 min.

Photo: © Katerina Valdivia Bruch

Katerina Valdivia Bruch is a Berlin-based independent curator. She has curated exhibitions for a number of institutions, including CCCB (Barcelona, Spain), Instituto Cervantes (Berlin and Munich), Instituto Cultural de Leon (Mexico), Para/Site Art Space (Hong Kong), and the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts. In 2008, she was co-curator of the Prague Triennale at the National Gallery in Prague. Besides her work as a curator, she contributes with essays and articles for art publications and magazines. Since 2009, she has organised a number of talks and exhibitions on Indonesian contemporary art. Her latest project Moving Images from Indonesia was presented during the sessions ‘Curating in Asia’ of the exhibition The Global Contemporary – Art Worlds After 1989 at ZKM – Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. Currently, she is doing a curatorial residency at the Langgeng Art Foundation in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Similar content

from - to

10 Jun 2011 - 18 Sep 2011

from - to

17 Sep 2011 - 05 Feb 2012