Cross-cultural influences shape the island of Sumatra

[caption id="attachment_6565" align="alignright" width="360" caption="Crown_of_the_Sultan_of_Siak"]

[caption id="attachment_6565" align="alignright" width="360" caption="Crown_of_the_Sultan_of_Siak"]Senior Curator of the Asian Civilisations Museum Singapore, Ms. Heidi Tan, shares in the following interview her high points in working together with the National Museum of Indonesia and the Museum Volkenkunde (National Museum of Ethnology), Leiden, in the first international travelling exhibition on Sumatran culture "Sumatra: Isle of Gold". The exhibition first opened in Jakarta in 2009, showcased later on in Leiden, the Netherlands and ran from 30 July to 7 November 2010 at ACM. It is a presentation of the unique culture and identity of Sumatra, especially the cross-cultural influences that have shaped the island from ancient times to the present day.

With regard to the travelling exhibition, can you tell us how ACM’s partnership with the National Museum of Indonesia and the Museum Volkenkunde (National Museum of Ethnology), Leiden came about?

As members of the ASEMUS (Asia Europe Museum Network initiated and financially supported by ASEF), we meet regularly at different forums which ASEMUS organizes. We have been speaking to both of these institutions for many years and we have been borrowing objects from each of these institutions.

As early as 2000, we had a major loan of Indonesian bronzes from Museum Volkenkunde. In 2003, we also had a major loan of bronzes for our exhibition, On The Nalanda Trail: Buddhism in India, China and Southeast Asia which examined the history of the transition of Buddhism from India to the rest of Asia. A few years ago, that exhibition went on show at the National Museum in Jakarta. The same show returned to ACM in late 2007. So we have had a very productive working relationship with each other for many years.

Just out of interest how and where do such major partnerships and collaborations begin?

It all starts over coffee! Or usually during a coffee break in the middle of a seminar or workshop which the ASEMUS organizes. Sometimes it’s really by chance. Sometimes it begins with an idea where perhaps a certain partnership might work if our resources were combined. So it happens through this network of friends and peers, all connected by ASEMUS.

Sometimes you get a proposal out of the blue and the key concern for us is always about how to adapt these ideas in the context of Singapore – how we can make this meaningful to our local audiences. We don’t just cut and paste a show or a concept from overseas. Instead we rewrite the wall text, for instance, or add more to the collection for local relevance. In the case of this exhibition on Sumatra, we have added about a hundred artefacts from our own collection.

This exhibition features over 300 objects which reflect the unique culture and identity of Sumatra, can you tell us how these artefacts were deliberated and chosen?

Well, the concept for this show was originally put together by the curators in Leiden and Jakarta. They worked on the idea for several years and we had to wait a couple of years more before the show finally reached our museum in Singapore.

They chose the best objects from their collection which represented the diverse Sumatran identity. However, when we started to think about adapting the show for Singapore, we decided that we needed to be very selective. We wanted to make sure we had room for our own artefacts as well. In fact, there were certain areas we wanted to add, for instance, the Chinese Collection. I went to Jakarta and actually chose a few more objects from their collection which were originally not in the show. I chose them because I thought they would strengthen that particular section. We also approached some private collectors in Indonesia and Singapore to incorporate a few tribal artefacts to enrich the Regional Exchanges section. So this is a really good combination of institution and private collections.

How are we looking at the ancient links between Singapore and Sumatra, both being significant international trading ports throughout SE Asian history?

There are strong links between Singapore and Sumatra which can be examined through one of our most interesting and important piece - the Crown of the Sultan of Siak (dated aprox. 1905). Siak, on the map, is directly opposite Singapore. It played an important role in the trade between Singapore and central Sumatra for a long time. In a popular analogy it is said that goods from all over the world passed through the mouth that was Singapore, then down the throat which was Siak and then upriver to the stomach which was Central Sumatra. That is just one instance which demonstrates the relations; Singaporeans have many connections with communities in Sumatra. During the colonial period and onwards, many who travelled from Aceh and other parts of Sumatra on the Hajj pilgrimage traditionally came through Singapore to catch a ship to get to Mecca. Today they catch a flight instead.

The legendary history is very interesting too. Legend has it that Sri Tri Buana, a Srivijayan Prince descended from the heavens, rather like a Bodhisattva and turned the ground to gold. He then travelled to the Riau islands and sailed around the archipelago, came across an island and spotted a strange creature. Upon enquiry he was told the creature’s Sanskrit name “Singha” and named the island Singhapura which until then was generally considered part of Sumatra. In popular folklore and in our history lessons, the Prince is also known as Sang Nila Uttama. But it is from this early lineage of royalty that a trade network sprung from the maritime kingdom of Srivijaya, and Singapore was an integral part of that trading network.

In what ways does this exhibition examine the complexity of the various cultures which have been influenced over time in Sumatra by the Indians, the Chinese and the Europeans?

The exhibition is split into Indian, Chinese, Islamic, Tribal or Regional and European sections of influences. These sections showcase sculptural artefacts, maps, miniature models in silver or wood from the colonial period as well as trade textiles which express cultural exchange through the centuries. Chronologically, there are some overlaps. The Indian influences could have started from the early centuries; the high point came when the Hindu-Buddhist kingdom Srivijaya flourished between the 7th and 13th century. The Chinese were also exporting goods in the region around that time. They only started shipping around the 10th -11th century. Until then, they relied on Indian and Arab sea traders to deliver their goods.

The Chinese were very keen on importing exotic products such as Kingfisher feathers, resin, bees wax and Kemenyang (aromatics such as benzoin or camphor) which they used for incense. So the Chinese communities settled early on, particularly after the voyages of Zheng He, the imperial eunuch, during 14th century. Zheng He had established tributary trading connections between local rulers and Chinese emperors. Peranakan origin can be traced to these early Chinese settlers. The influence of Zheng He created an influx with the Malay and Indian communities too.

Of course there have been waves of migration since then; the Portugese, Dutch and English arrived in the 16th, 17th and 18th century respectively and fought for the control of trade (of pepper especially), in and around the region until they resolved their conflicts by way of the Anglo Dutch treaty in 1824. The Dutch swapped Singapore for Bencoolen on the West coast of Sumatra whose then governor was Sir Stamford Raffles.

In the 19th century, European ethnologists came to study the flora and fauna as well as to map the region and understand its people so as to better control them. They took back to their empire not just samples of plants but also miniature models of the architectural styled dwellings and everyday objects, some of which are on display. One of the exhibits is a miniature model of the Sultan’s Naga-shaped ceremonial vehicle complete with royal regalia and Dutch flags.

Each section parlays the waves of religious influences adapted from the early Hindu-Buddhist traditions to Islamic and later Christian conversions in recent history.

Which pieces would you consider the highlights of this show?

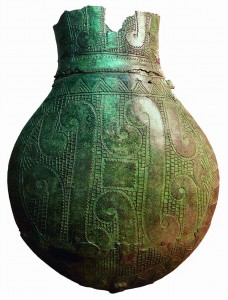

[caption id="attachment_6648" align="alignright" width="228" caption="Vessel"]

[/caption]

[/caption]Our oldest piece on display is a bronze vessel or a large ‘flask’ forged 2,500 years ago. We do not know what it may have been used for but its flat elliptical shape, adorned with spiral and hook patterns suggests it could have been carried around by the earliest settlers, the Austronesians, who migrated by boat or canoes from South China and Taiwan 6,000 years ago and brought with them bronze casting techniques between 300 BCE and 500 CE. This vase is from the collection of the National Museum of Indonesia. Extremely rare and elaborately decorated bronze bracelets, earrings and anklets from the same period are on display as well. These ornaments were status symbols as bronze casting was a high tech business for that time considering the hands-on labour involved.

There are also the songkets, ceremonial shoulder cloths which are sumptuous textiles worn for rituals. These cloths, woven in the Indian tradition were traded or gifted to royalty and further embellished with gold leaf and gold threadwork. In the Islamic Influence section is a collection of royal regalia - the Crown of Siak, a scabbard and a dagger forged with iron and gold incorporating Chinese, Hindu and Islamic motifs and design. Emblematic of royalty, these objects were associated with supernatural powers which were conferred on the king legitimizing his right to rule.

The Dutch later confiscated these symbols of royal power to assert their authority over Sumatra, which is how a number of these objects ended up in the Dutch collection. Over the years, some have been returned and the Dutch and the Indonesians are working together on cultural exchange projects. In fact this exhibition started as collaboration between the Leiden Museum of Ethnology and The National Museum of Indonesia, both of which are friends of ACM through the ASEMUS network.

A concise history and catalogue of this exhibition has been compiled by the above mentioned institutions in collaboration with the ACM (available at the museum’s gift shop).

Bharti Lalwani has an MA in Contemporary Art and writes for publications such as Asian Art News and www.arterimalaysia.com, curates on occasion and is currently developing art education approaches for children under 10 years of age.

Similar content

posted on

30 Nov 2011

from - to

21 Apr 2012 - 21 Apr 2012

from - to

05 May 2012 - 11 Nov 2012

from - to

15 Nov 2011 - 03 Jun 2012

24 Jun 2016 - 26 Mar 2017