Culture and arts as a bridge between Central Europe, Southeast and East Asia

The ASEF LinkUp | Asia-Europe Cultural Diplomacy Lab 2024 was held in the capital of the Czech Republic, Prague, making the center of Central Europe the first location outside of Asia to host the Lab. The project served as a meeting point for selected participants from the cultural and governmental sectors and the Asian participants came from Southeast and East Asia.

In this article, written as part of ASEF culture360 and the European network on cultural management and policy (ENCATC)'s Arts Journalism Matters Fellowship 2024: Virtual x Prague, I would like to explore how culture and the arts can bridge (and in some cases have already bridged) Central Europe and Southeast and East Asia, areas that seem so far apart.

If you were to ask an ordinary person from Central Europe - meaning the geographical area of Europe, as these countries share many cultural similarities rooted in common history - about any significant moments between their country and any country in Southeast and East Asia, you would probably be met with silence. Of course, most of the Central European countries are landlocked, so in the past it was harder to establish links between them and Southeast and East Asia - and vice versa. But what about now? Although the distance remains the same, the world in general has shrunk and there are many ways in which people from different countries and cultures can meet. So how can culture and arts bridge Central Europe and Southeast and East Asia?

The starting point may seem a little sad. But the lack of a shared past between these regions can be a good thing. Think of it as a tabula rasa, a blank canvas, inviting everyone to write, paint or draw new stories. Everyone is equal in this situation, there is not much need to discuss the power dynamics that can easily be found in projects and relationships between countries with colonial and imperial pasts. In this article, I would like to mainly investigate the relationship between the Czech Republic (and its former institutions) and Southeast and East Asian countries. At first, are there really no stories between these places that are thousands of miles apart?

1. The courtyard of the Czech Ministry of Culture, which served as one of the places where this year's ASEF LinkUp conversations took place © Vojtěch Pulda

Stories from the past and the present - already established cultural links?

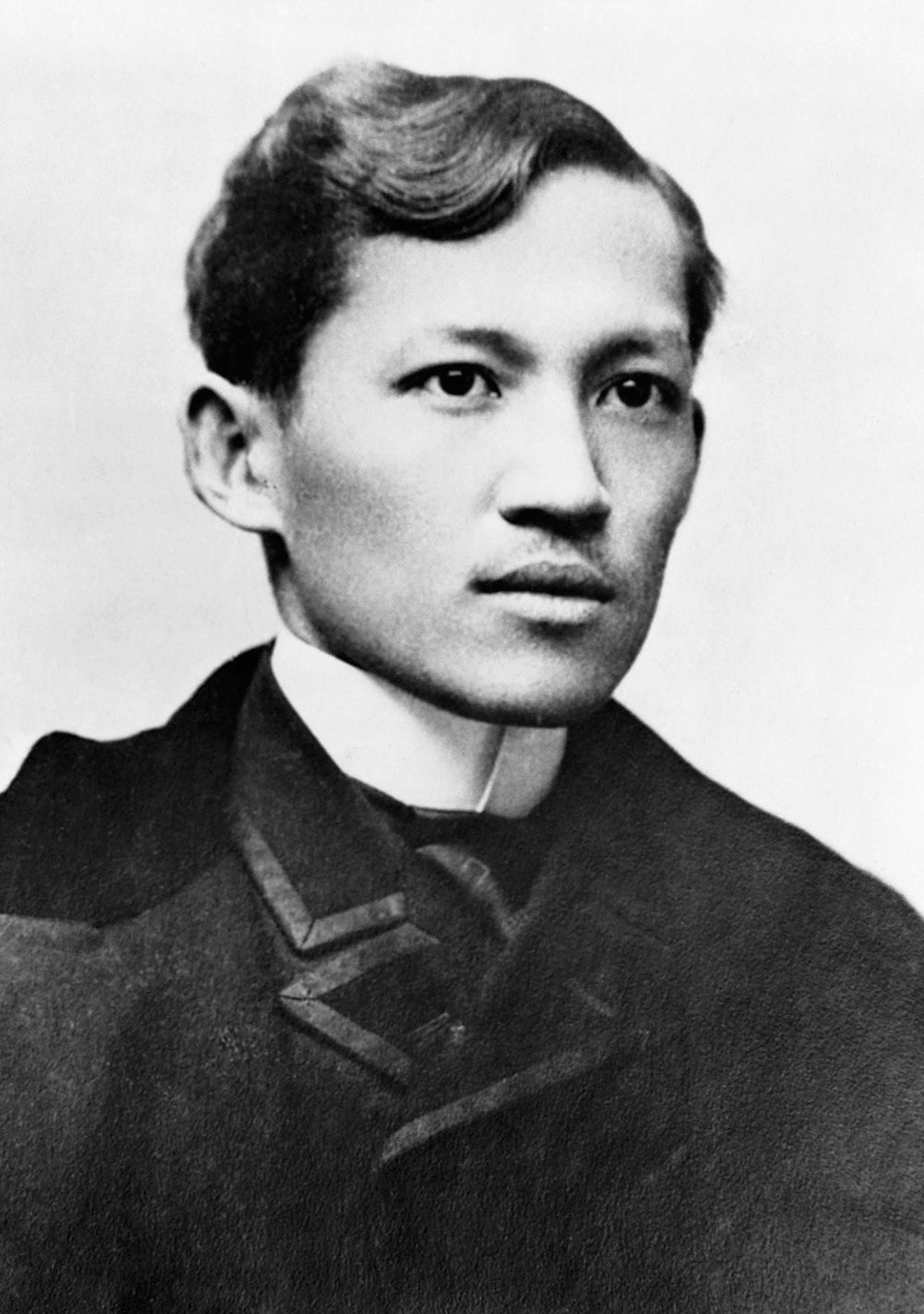

Let's start by exploring a story from the past. José Rizal was a man of many talents. One could say that he was a modern renaissance man. Doctor by profession, poet, writer, polyglot and ultimately the national hero of the Philippines, whose ideas and spirit inspired movements that led to Philippines‘ independence. Perhaps surprising for some, there is a direct link between Rizal and the Central European region. Rizal spent several years in Europe and made contacts with like-minded people.

The most important and closest was with Ferdinand Blumentritt, a secondary school professor from Litoměřice. Blumentritt was deeply interested in the Philippines, and although he never visited Rizal's homeland, he was an active publisher of articles about the country. The two men became close friends and their friendship lasted until Rizal's execution in 1896. The importance of this friendship can easily be seen in the fact that Rizal only wrote two letters the night before his death – one to his mother and the other addressed to Ferdinand Blumentritt. This important connection is often overlooked in the Central European region. Perhaps it is harder for us to imagine such a situation happening, although this record shows that even a hundred years ago, in times before the internet and social media, the distance between nations was irrelevant.

Another aspect is Blumentritt's national identity. He is a great example of the complicated nature of national identities in the Central European region. Although he lived all his life in (what is now) the Czech Republic, he clearly had a German surname and his first language was German. Later, after the Second World War, Blumentritt's son Friedrinch was one of many people expelled from Czechoslovakia (present day Czech Republic).

2. José Rizal - the national hero of the Philippines © Wikipedia

Another example is about the power of sports in connecting people. It is not often that a person from a small country like the Czech Republic becomes a sensation and a cultural icon in the East Asian region. But that is what happened to Věra Čáslavská.

Čáslavská was a Prague-born gymnast who became the star of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. It was her powerful performance that made her an icon. She won three gold medals and was nicknamed 'the flower of the Tokyo Olympics'. To this day, her legacy remains popular in Japan, especially among the older generation, and in 2010 she was honored with the Order of the Rising Sun. It was Čáslavská who contributed to the deepening of Czech-Japanese relations. One would have expected her spirit to be held in high esteem at that time, but unfortunately it was quite the opposite. Věra Čáslavská was one of the signatories of the "Two Thousand Words" manifesto and became a symbol of the struggle against the former regime in her motherland. Today, almost a decade after her passing in 2016, she rightly remains an icon in both Japan and the Czech Republic and is often mentioned as a cultural bridge between these regions.

At last, moving into the present. Apart from the discussions taking place at ASEF LinkUp in Prague, participants had the opportunity for several site visits and networking opportunities. In addition to the perhaps obvious ones, such as the Ministry of Culture, there was a trip to Plzeň (Pilsen). A festival was held there at the time. Skupova Plzeň is the oldest professional theater festival in the Czech Republic. It focuses on puppetry and alternative theater. The roots of the festival go back to the second half of the last century, when it was founded on the occasion of a double anniversary (the 75th anniversary of the birth and the 10th anniversary of the death) of the puppeteer Josef Skupa.

It goes without saying that not only Czech puppeteers presented their art. The festival has a long tradition of (East) Asian participation, with this year's artists coming from Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia (as well as the United Kingdom, Slovenia, Slovakia and Poland). It is important to note that traditional forms of Indonesian puppetry have found their way into Czechoslovak puppetry traditions. To put it simply, there is something about puppetry.

We can find this art form in all corners of the world, it transcends borders and languages. It's festivals like Skupova Plzeň that are proof that sometimes you don't need language to have a full understanding of each other's stories. All these stories, past and present, show that there are already several links, perhaps building blocks for future connections, that can help bridge Central Europe and Southeast and East Asia. Whether it is a friendship that transcends distance, a sporting spirit that has captured the hearts of many, or a celebration of a shared art form, they mark deep and personal cultural links between these regions. In the spirit of the ASEF LinkUp, one has to therefore ask themselves, is this all part of cultural diplomacy?

3. As part of the Skupova Plzeň Festival, you could see a unique collection of wayang golek - a traditional form of puppetry from Indonesia. This form inspired a type of puppet that can be found in Czech puppetry. This type of puppet is called "javajka" - a reference to the Indonesian island of Java. The collection belongs to the Czech theatrologist Jana Wolfová. © Wikipedia

Notes on cultural diplomacy

The term cultural diplomacy just feels good to say. However, its meaning can vary and it is also a highly contextual term. Sometimes referred to as 'soft power', this attribute in itself also carries a somewhat problematic undertone. Unlike other types of diplomacy, cultural diplomacy is seen as something pleasant, but at the same time there can be a transactional expectation. An example of this are the cultural centers that many countries around the world have as an essential part of their cultural diplomacy and relations program. However, these centers often - if not always - fall under the responsibility of Ministries of Foreign Affairs or similar bodies.

While this makes sense in some ways, based on several conversations with the participants of the Lab, there is likely to be a transactional expectation that favors projects and initiatives with visible and easily measurable economic benefit and impact. Culture is a part of our lives that is tangibly displayed, but is highly intangible in nature - so how do you measure the impact of something like that?

It will take a lot of rethinking to figure out how to do it. But one thing is clear. Projects that at first glance do not have a visible economic benefit or easily measurable impact should not be neglected. Think long term and do not underestimate people-to-people interaction. It is often these projects that can have a greater impact in the long term – more than initiatives that have been created with an economic benefit in mind. Culture and the arts depend on people, and there must be spaces where cultural practitioners (in the broadest sense - from artists to journalists to cultural policy makers) can meet. Not necessarily for the culture-for-culture sake but rather for the sake of the future and establishing connections for cooperation.

ASEF LinkUp in Prague was a good example of this. The group worked towards a final document of recommendations, but it was the people-to-people interactions that would eventually make a huge and lasting difference. Having a space where cultural practitioners and government sector representatives can meet and discuss challenges and solutions was extremely beneficial, as it turned out that participants (regardless of cultural and professional background) were and are facing similar issues in their practices. This in itself, unironically, can bridge many distant countries.

Future of Central European and Southeast and East Asian cultural relations

As shown above, there are already links between Central Europe and Southeast and East Asia - and these few examples 'only' come from the area of the Czech Republic. If we were to look further, we would certainly find more of these stories in the Central European space.

One thing is certain: the distance between these places should not be a disqualifying factor for intercultural cooperation and relations.

Quite the opposite. This blank canvas offers a good starting point, as the particular challenges of building new relationships will be similar, but it has to be done right. One of the topics discussed during ASEF LinkUp was scaling. Especially in Central Europe it is important to nurture existing links and build from there. These connections have been made without any economic benefit, but rather based on interpersonal interactions and a genuine interest in something in common.

Go big or go home may simply not work here - projects need to make sense (creating huge cultural events out of the blue that are not rooted in anything substantial may do no-good). Finding these stories, past or present, can therefore be highly beneficial, as these potential grassroots projects will be of great nurturing value for future initiatives down the line. They also create opportunities for people to connect. A holistic approach is another matter.

Based on several conversations during ASEF LinkUp, it is not uncommon for a government body and the actual 'field' cultural practitioners (for example cultural managers, artists, community workers etc.) not to meet. This creates a huge gap between theory and practice. Especially in projects that try to bridge regions that have not worked together before, a communication barrier can be fatal. It may sound obvious, but the openness to dialogue and listening is the crucial point here. To try to answer the question posed at the beginning on how culture and arts bridge Central Europe and Southeast and East Asia, we must start by acknowledging that there are already links between these two regions. Yes, they may be modest, but they are strong, and they are built on genuine human connections. It is the interaction between people that is often underestimated.

There is also a perception that the general public is not interested in these projects, but it is often the case that the stories that bridge two different and distant areas are not told. This is related to the cases mentioned earlier about projects that (at first glance) have no economic value. These grassroots projects should therefore seek to create new links on a cultural level - essentially developing and nurturing existing seeds of previous endeavours.

To sum it up: the world is much smaller than it was decades ago, and we all face global problems together. So there should be projects that try to connect places that seem to have nothing in common, but as we have seen, if we dig deeper, there are strong links and connections.

It is important to seek these links, nurture them and create opportunities for intercultural dialogue. After all, culture and art are created on the basis of real interactions and feelings between people – connectedness and relatedness are core to humanity.

About the Author

Vojtěch Pulda is currently a master's student at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic. Since his early years, he has been interested in different cultures from all over the world and the enriching power of culture-sharing. He completed his BA in Humanities in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in postponing his dream of working in the arts sector.

Three long years and two corporate jobs later, he decided to return to university and continue his education in the field he is most passionate about. His main study focus is on museums, presenting both tangible and intangible heritage within these institutions and public spaces, intercultural dialogues, and the more practical and hands-on aspects of working in the arts sector. After his master's, he would like to explore the possibility of continuing his education with a PhD program that would focus on transcultural matters, cultural entrepreneurship, and how to make culture and heritage sharing more accessible globally.

ASEF culture360 and the European network on cultural management and policy (ENCATC) are delighted to collaborate on Arts Journalism Matters Fellowship: Virtual x Prague, aiming to provide capacity building, networking and collaboration opportunities for young emerging arts journalists from Asia and Europe.

This edition launched with a 3-week virtual residency with Dr Carla Figureira and the participants met in Prague to cover the 2nd edition of ASEF LinkUp | Asia-Europe Cultural Diplomacy Lab, a 4-day event from 10 to 13 June 2024.