By Kerrine Goh

Film success in small countries – from Scotland to Singapore

What counts as a ‘successful’ film (industry) inevitably means different things to different people. Nonetheless, when it comes to building a sustainable domestic film sector for cultural or economic reasons or both, small countries around the world face similar challenges in countering the hegemony of regional and global film ‘superpowers’. Whether competing with Hollywood, Bollywood or Nollywood for audience share there is some evidence, from Europe at least, that smaller countries’ patterns of success are in fact remarkably congruent with each other and with the industrial giants.

Our research at the Institute for Creative Industries at Edinburgh Napier University has been looking at the relationship between levels of film production in small countries (i.e. with a population less than 10 million and particularly those, like Scotland or Singapore, with a population in the region of 5 million); the proportion of films which become box-office hits; and the share of the national audience achieved by indigenous films overall.

The experiences of Scotland, Singapore or Denmark are unique in many respects but similar in some. Scotland and Singapore share a complex cultural and economic relationship to their near neighbours, reflected in the fortunes of their media sectors. As an English-speaking ‘stateless nation’ Scotland’s intimate cultural, fiscal and political relationship to the UK means it lacks a distinct film market of its own (unlike say Catalonia’s position within Spain). Though independent since 1965, Singapore has a similarly complex cultural-linguistic-economic position within South-East Asia, having both built and partially lost a significant domestic film industry. In contrast Denmark, a relatively self-contained and autonomous nation-state for centuries enjoys the highest domestic box office share of any small European country.

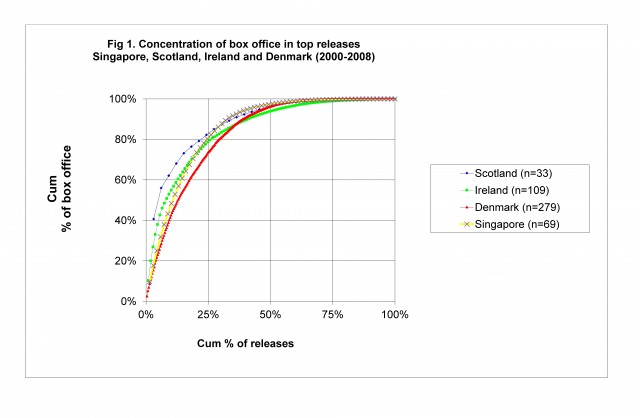

Looking first at the European experience we found that the same heavily skewed pattern of success that researchers have found in the USA and elsewhere – where 75-80% of box office revenue is generated by just 20-25% of films - is replicated in small countries. This is true both for the market as a whole (typically comprising 80% or more Hollywood product) and, considered separately, locally produced films. This ‘scale-independent’ effect can most easily be seen when we graph (figure 1) the proportion of titles generating the largest share of the total box office for locally produced movies in three small European and one Asian country.

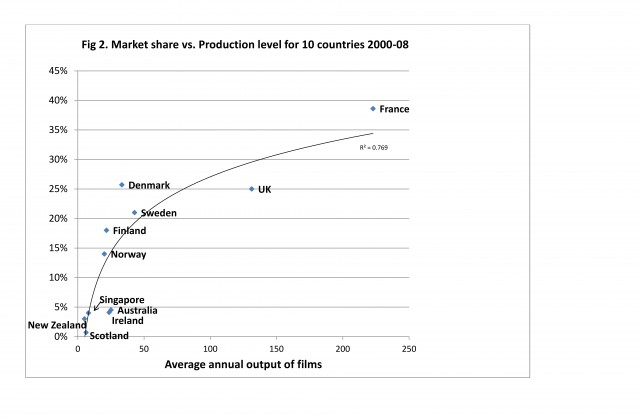

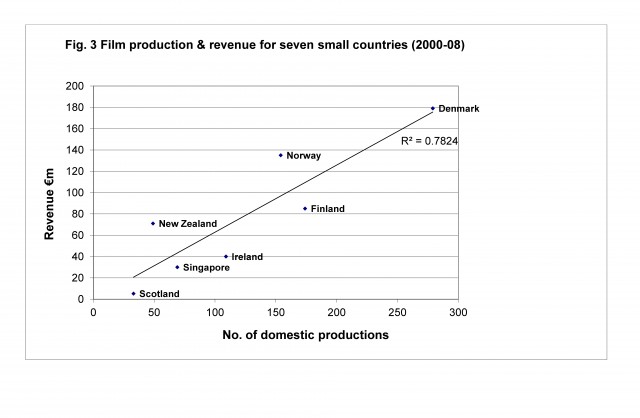

The perhaps less surprising pattern that also emerges (figure 2) is that higher levels of local production tend to correlate with a higher share of the domestic box office (which although only accounting for typically 25% of a film’s total revenue, remains a very good predictor of overall revenue from distribution across different media such as DVD and Video on Demand).

However in very small countries (like Scotland with a population of around 5m) producing just a handful of films a year (in Scotland’s case typically six) these relationships are easily masked by extreme annual variations. In small countries individual years’ combined box office for indigenous films can vary so widely as to appear completely unpredictable, chaotic even. Indeed in a very important respect individual film success is, as extensive research has shown, literally unpredictable. The ‘portfolio effect’ of producing in volume allows major studios to turn an apparent game of chance into a reasonably reliable business model. We know how Hollywood built success upon success: using vertical integration, an influx of European talents, sound, the weakness of post-WW2 European industries and so on to consolidate its grip on much of the world audience. We also know that independent producers and small studios in many parts of the world have been and remain highly susceptible to ‘boom or bust’. For these reasons European countries both large and small have, since the 1940s, deployed public subsidies to ensure audiences are able to access the range of films that policymakers imagine (perhaps naively) that one day a sustainably self-reliant film industry will supply.

Against this background commonsense alone would probably suggest that in order to increase its share of the domestic audience a country needs to produce more films. However at small volumes of annual production the great variability in apparent success (critical or commercial) tends to focus public and policy-makers attention on ‘making better films’ as much if not more than ‘making more films’. Indeed there is sometimes a tendency to say ‘why pour good money after bad’ if there have been a string of poor years. Hindsight tends to trump more rigorous analysis in this field and there is a popular tendency amongst journalists and pundits to blame the producers or, where public funding is involved, the film-agencies or both for their evident errors of judgement in greenlighting this or that film. Producers are in turn equally likely to blame distributors for not marketing their films heavily enough or indeed for not releasing them at all – in the UK typically 50% of features get little or no theatrical distribution. When journalists, pundits and rival filmmakers pour over the entrails of ‘yet another flop’ (or conversely a surprising success), film policy debates tend to focus on how changes in strategy can promise ‘more winners’ for the same amount of investment rather than consider the less politically palatable suggestion that the level of investment itself is the critical factor.

Yet the evidence suggests that over time the share of domestic audience tracks the level of output in a fairly consistent way, bearing in mind the problem of ‘chaotic’ behaviour at low volumes of production. Taken together the apparently constant ratio of hits to flops; the general unpredictability of individual films’ performance; and the positive relationship (up to a point) between output and audience share, we must surely conclude that raising production volume is indeed a necessary (though not necessarily a sufficient) condition of improving box office, if not critical, success.

Of course this is not to suggest that blindly increasing the film output of a small country by pouring public (or private) money into production funds will automatically generate an ever larger share of the domestic audience. The dynamics by which public tastes and film-going culture develop and interact with the products of both the domestic and global industry over time and space in a given, ‘peripheral’ nation or region are undoubtedly complex. Increased production investment alone will not produce the hoped for increase in audiences, acclaim and economic impact. Education, skills and talent development are just as important as (and no less costly than) financial incentives, tax breaks and subsidies.

[caption id="attachment_5817" align="alignright" width="210" caption="Main cast of hit series "The Inbetweeners"."] [/caption]

[/caption]

To bring these factors together small countries’ policy-makers need to focus on how overall production can be increased while simultaneously ensuring a plurality of talent, businesses, genres and audiences are cultivated. The next big film is as likely to come from a relative unknown as from a heavily-backed director or studio. The current UK chart-topping The Inbetweeners is a very good example of this at work. The seventh film by a Scottish-based producer but the first of his to achieve any commercial success, it has already taken over £35m at the UK box office alone, ten times its budget of £3.5m. Such success creates neither precedent nor formula and indeed should remind us that in William Goldman’s phrase ‘nobody knows anything’. But what we do know is that small countries can produce successful films and substantial audiences for them but do so consistently requires critical mass.

About the Contributor

Professor Robin MacPherson is Director of the Institute for Creative Industries and Screen Academy Scotland, one of three Skillset-accredited Film Academies in the UK. In 2008 he established ENGAGE, an EU MEDIA-funded international development programme for writers, directors and producers which, with MEDIA MUNDUS support from 2011, has expanded to work with film schools in Asia and North America. He blogs at www.robinmacpherson.wordpress.com and is a Board Member of Creative Scotland

Similar content

posted on

posted on

posted on

posted on

posted on

posted on