Virtual360 Konnect | Spring[s] for Democracy

Ei Arakawa & Inza Lim, The Unheroed Theater, 20142020, installation view.

Courtesy of the artists and Gwangju Biennale Foundation

An article by Soo Young LEAM from Korea and Kathleen DITZIG from Singapore, participants of the Virtual360 Konnect - Emerging Arts Leaders Virtual Residency Series, on their joint project.

Spring[s] for Democracy Q & A: What does it mean to think about May 18 Gwangju Uprising (1980) in the time of Covid-19?

Soo Young LEAM from Korea and Kathleen DITZIG from Singapore participated in the Virtual360 Konnect - Emerging Arts Leaders Virtual Residency Series from 28 September to the end of October 2020. The pair have been working on Spring of Democracy, an exhibition curated by Ute Meta Bauer. The exhibition, commissioned by the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, was part of a broader project, MaytoDay that commemorates the 40th anniversary of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising.

For the Virtual360 Konnect residency programme, Leam and Ditzig developed a project based on a series of posts, known as Spring[s] for Democracy. Inspired by their work on Bauer’s exhibition, the series can be read as the geeky personal musings of two researchers responding to an exhibition. As digital markings, this series was a speculation of how researchers can collaborate in a time when being together is literally impossible. The following exchange unpacks their collaborative experience while working on an exhibition in the time of COVID-19.

Soo Young Leam: This year marked the 40th anniversary of May 18 Gwangju Uprising. When we first began work on MaytoDay commemorating the historic – yet still highly contested – incident last year, we didn’t expect anything like COVID-19 to take place. How has your experience of working on the exhibition been? What were your concerns and newly raised questions in working with unforeseen circumstances?

Kathleen Ditzig: We started working on this project with a research trip in October 2019, and had planned a number of trips after for installation when the exhibition first opened in Art Sonje Center in Seoul in May and then more recently in Gwangju. Ute said to me that this was the first exhibition that she curated where she was not onsite itself for installation. I think this remote process of organising an exhibition actually forces the stakes of collaboration to become much more integral to exhibition-making. Enabling the time and space for discussions for important issues became more than just pragmatic. These conditions meant that a deeper trust formed between us as researchers. I wonder if COVID-19 had not happened if we would have developed this research driven relationship. We could have been very pragmatic about collaborating but I think the more time we took allowed us to learn about each other’s research beyond our professional functions, such that we decided to do this in spite of how busy we are and such that we are actually now working on a larger project on East Asian and Southeast Asian de-colonial regionalism. In a nutshell, working on this exhibition has been one of my most rewarding and educational experiences to date.

Working through COVID-19 and the anxiety and precariousness of the early days of the virus, I was worried about our contributors, what it meant to make an exhibition in light of the world unravelling and what it meant for our shipping and production timelines (Though, working with you and the team at Gwangju Biennale Foundation left me with very little worries regarding the latter.)

Exhibition view of Spring of Democracy as part of MaytoDay.

Courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

The experience of COVID-19 on a global scale has been by definition ‘uneven’. Some countries have managed their outbreaks, others haven’t, and often the difference has come down to the political and moral systems that define specific societies. COVID-19 has been more deadly in some countries. I think given the nature of how international the art field is, we all know someone who directly has had the virus or been devastated by the virus. Having that anxiety and fear for people you care about and people you work with really re-orientates things. It also makes you question what is the more valuable use of resources in light of everything going on.

How about you?

SYL: I found the practice of respect and care all the more important in this process. The things that we’ve taken for granted, really came to matter. At every stage of preparing for the project, we needed to rely on each other to assess the ‘actual’ spatial conditions and make decisions because we were facing so many uncertainties, intensified by the sudden introduction of ‘emergency’ policies. And because the pandemic is inherently tied up with politics and ideology, going beyond the issue of health care, the exhibition’s theme was all the more sensitive and urgent. It allowed me to think about new ways of practicing cultural collaborations and critically reflect on the process of making the exhibition itself.

COVID-19 has given the government all the reasons and power to enforce its national borders and protect citizens by way of tracking their every movement. While many Asian countries, including Korea, have been active in utilising the latest mass surveillance technology to effectively contain the contagion, the violation of individual freedom and privacy still remains a central concern. The division of essential and non-essential work forces, as well as the categorisation of spaces into ‘highly dangerous’ and ‘relatively safe zones’ also had a profound impact on the cultural sector, whether in terms of its production system or modes of survival. This made me become more interested (and invested) in what I’d like to call ‘ways of gathering’. In response to constantly fluctuating conditions, cultural producers in Korea experimented with new ways of gathering audiences and ideas, be it through Virtual Reality technology, Zoom or temporary online interventions. For the Gwangju iteration of MaytoDay, we’ve recreated part of the exhibition in an online VR show, so that we can engage an audience unable to travel to the exhibition. The new challenges that we are facing are pushing us as cultural producers and institutions to become more creative and experimental as we find new ways to bring together people’s voices, ideas, and views despite the real difficulties that threaten our existence.

Because a lot of the works included in the MaytoDay exhibition not only deal with the history of May 18 itself, but explore broader questions like amnesia, flow of information, forms of clustering, post-truth, among others, I think the exhibition allowed us to assess the ‘new normal’ that we are being gradually accustomed to more clearly and critically.

Exhibition view of Spring of Democracy, Art Sonje Center, Seoul.

Courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

How has the pandemic changed the way you think about the May 18 Gwangju Uprising and more broadly, the issue of democracy? What do you think exhibitions can do in times like these?

KD: I completely concur with you. I think that the resurgent importance and power of the nation state in relation to civil society and in light of COVID-19 makes a reexamination of the uprising particularly pertinent.

COVID-19 and this project made me consider the importance of thinking laterally not just within the realm of art history but with regards to an expanded notion of mutual aid. It’s particularly exciting to see ‘mutual aid’ being taken up because the term is historically tied to a political project of defining another value and exchange system than competition-led capitalism. Art institutions have been inspired to address systematic occlusions and create opportunities for the marginalised. I have seen the Singapore state mobilise more commissioning opportunities and facilitate the digitalisation of the arts. (As an aside, one of the exciting things will be the many ‘archives’ of art projects that come out of this period. Yet, I am concerned like you are that there isn’t a wide understanding of the latest technologies - not just in how to use them but how they are used to govern us.)

At the same time as the state and the institution become more transparently the locus of resources and capital for cultural production, we need to think of mutual aid beyond the state. Especially because the response to COVID-19 has been so uneven around the world, I think we have to think about what it means to develop mutual aid across borders. This line of thought is inspired by how transnational support for the uprising was and how important South Korea’s democratisation became for other countries. One just has to look to our post on Kim Dae Jung and Benigno Aquino or our interview with the curator and art historian, Carlos Quijon Jr about people’s movements in South Korea and the Philippines to see the evidence of this.

In this regard, I think doing this during COVID-19 has given me an appreciation for how important it is to think about the writing of art history beyond the national framework and to think laterally about what is going on in relation to other communities within the larger political network of capital flows that define cultural production. One of the most fascinating things for me to discover in studying the Gwangju uprising and the biennale was the role that industrialisation and the economy played in the democratisation process - I mean this in terms of the crux of many of the issues coming down to labour in an international market place. A strong state is almost necessitated by a global capitalist market place. The Gwangju uprising grew out of protests by farmers and factory workers and is defined in part by a memory of a violent impression by a ‘strong’ state. The relation of the political and the economic is symbiotic.

With regards to the importance of thinking about the uprising and making the exhibition now, I think that the impulse to exhibit and display which is still acted out across the world’s institutions during COVID-19 points to its important role in civil society. Maybe I am naive for thinking this but I do believe that in such times of crisis, exhibitions can play an important role of reflection, reflexion and providing solace in inspiring an alternative world or in the case of the exhibition we worked on it can play an important role in pointing to a history that can be instructive in the present as we chart new social reforms. Moreover, exhibitions are historical objects and so we don’t just make them for the present, we make them for the future, for someone in the future who like us is looking to the past for a way forward.

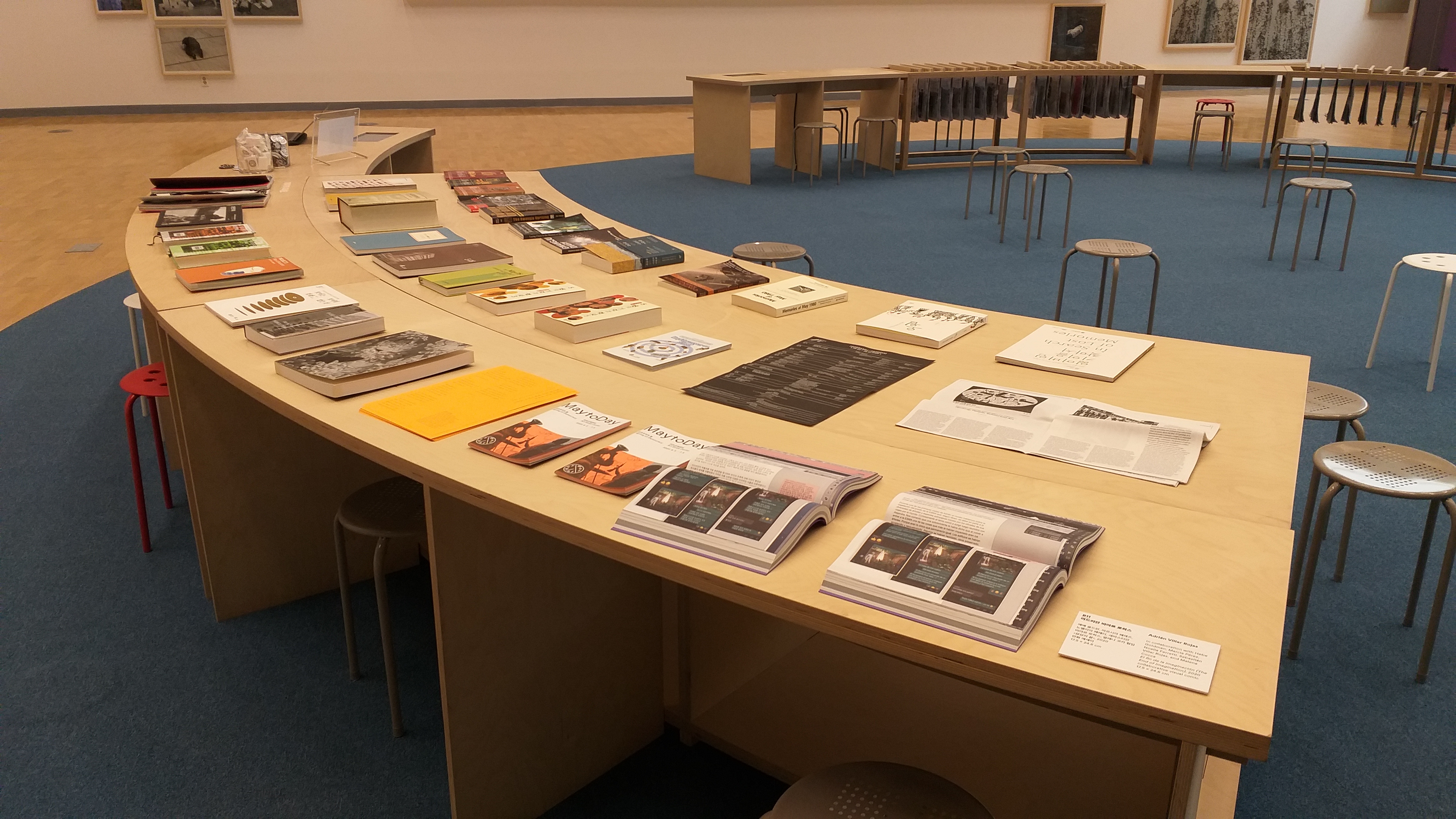

View of The Archive Desk at Spring of Democracy exhibition.

Courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

How about you? What was the resonance of this exhibition in South Korea? You have been submitting your PhD while we took on this project, how has this project shifted your perspective?

SYL: I agree with you on many points. Taking on this project during this unprecedented time has reminded me about the urgency of writing art history beyond the national framework. In this sense, I think the structure of MaytoDay, which invited curators from different cultural and geographic backgrounds was particularly meaningful. It was really inspiring to work with you because you were bringing in new perspectives into the history of May 18 as a non-Korean, expanding its discourse outside the local context of Gwangju. At the same time, it also made me realise the lack of English resources on May 18. You mentioned earlier about the proliferating archives (especially the digital ones), and this reminds me of extra layers of complexity we had to face to make certain archival materials available. The issue of accessibility, in this regard, speaks on many levels. I’m not only saying this in terms of accessibility of information and knowledge, but the kind of accessibility we would have to offer to eventually overcome the new barriers and borders that have been set up between nations, social groups, ethnicities to ‘fight against’ the virus. The significance of accessibility - perhaps a notion I’ve been taking for granted - can also relate to the idea of ‘mutual aid’ you brought up earlier.

Although my PhD thesis deals with a particular artist from South Korea and the (un)doing of sculptural practice from the post-war period to the present day, my involvement in the project and life under COVID-19 have allowed me to witness first-hand how artists are able (or equally unable) to respond to the kind of ruptures that we are experiencing. I wonder how might we, as art historians or curators, revisit this period in the future and contextualise the cultural milieu formed in response to COVID-19.

This article is part of a series of articles written by the participants of Virtual360 Konnect - Emerging Arts Leaders Virtual Residency Series, an online cultural exchange and capacity building initiative developed by the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) and the ASEAN Foundation through KONNECT ASEAN. Over a period of one month, 20 emerging art leaders from Korea and 5 countries of the ASEAN region (Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines and Singapore) collaborated in pairs on the theme of international cultural exchange in the Covid-19 era.

Similar content

18 Oct 2020

posted on

29 Jun 2020