India: media piracy-intellectual property interview

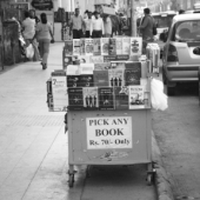

[caption id="attachment_2750" align="alignright" width="240" caption="Lawrence Liang, 2007. Photo credit: flickr.com/photos/joi/564334544/"]

[/caption]

[/caption]Interview with Lawrence Liang, Alternative Law Forum

Lawrence Liang is a researcher and writer based at the Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore. His areas of interest have been in the intersection of law, culture and technology. He has worked closely with Sarai, New Delhi on a joint research project - Intellectual Property and the Knowledge/Culture Commons. Liang has authored the "Guide to open content licenses" in 2004. He is currently working on a book on law and justice in Hindi cinema.

Siddharth Chadha has interviewed him on the relationship between Intellectual Property Debate and Media Piracy.

Siddharth: What is the role that non legal technologies have played in changing socio-economic environment in India since the 90’s?

Lawrence: Could Bangalore have become an I-T city without non-legal software? Absolutely not! If you ask any of Bangalore's engineers where and how they learned their computer skills, you will get only one answer - all these people acquired their computer skills through non-legal software. This infrastructure of Bangalore as an IT city - a lot of it is built on non-legal media, and this is completely unacknowledged.

If you look at the history of India and the question of knowledge and ask who has access to knowledge? There are exclusions on the basis of gender - if you look at most of the IIT's and other engineering colleges, there are mostly male students. There are exclusions on the basis of caste - by and large, only upper caste people can go to engineering colleges. So, when it comes to this monopoly of knowledge, the hierarchies in India are already set. In my mind, these non-legal technologies and media open a lot of avenues. It gives those who don't ordinarily fit into the knowledge economy a chance to participate on their own terms.

Siddharth: Piracy has brought about individuals into direct legal conflicts with the big media companies? Is there a way to resolve this battle?

Lawrence: The relationship between law and technology has always been like this. When photography was invented, there was this crisis. You may not know this, but at the time when the VCR was invented, Universal Studios sued Sony in America. They demanded that the VCR be banned, because it enabled you to record TV programs, thereby violating copyright. Imagine what would have happened if they banned that technology... the large VCD and VCR industries would all be dead.

Siddharth: In the new legal property regimes, why is Intellectual Property in a state of crisis?

Lawrence: The problem with information is that it is not like a pen. Take a look at this pen - if I am using it, then you cannot be using it. And if you take it away from me, then I no longer have the pen. But information is not like this - Information is an intangible good. If I have an mp3 and I give you a copy, or email it to you, then the mp3 that I have, is also with you. Economists call this non-exclusive or non-rivalrous use. Non-rivalrous means that your use of something doesn't compete with my use. you can use it and even I can use it. The world of ideas is always like this. The world of ideas spreads through sharing, through copy culture.

Video: What do you think of media piracy?

Siddharth: Is it true that the world of ideas spread through copy culture?

Lawrence: in the 1950s, Hindi film songs were extremely popular in Greece, and many Greek songs were copied from hindi film songs. Similarly, if you look at this one song, Dil Tadap Tadap Se Keh Raha Hai from the movie Madhumati, it is copied from a Polish folk tune. The world of culture and creation is always spread through copy culture. We need to conceptually, make a distinction. When people look at a copy, they see it with a negative view. They perceive it as being fake. They look at copy as a dilution.

Siddharth: But what about the artist? Doesn’t the author of the work stand to lose in a free sharing world?

Lawrence: Copyright's discourse and popular myth says that this money is going to the artist. But in reality, the artist rarely benefits from his sales. You need to understand one thing about Copyright - there is a distinction between the creator and the owner that is extremely important. The creator and owner is very rarely the same person. If I created a song and am the author, it doesn't mean I am the owner of the copyright. Because when I sign a contract with a large company, I assign them the copyright. So, I get a flat fee of 100 rupees, yes? Let's say I'm Arundhati Roy and I have written the God of Small Things. I've received a large advance sum. I may get 4-5% in royalties, but 90% of the profit goes to large companies.

Even I write books. I get 0% royalty. I have never made money from my writing.

Liang is the author of A Guide To Open Content Licences. This is described as a guide to how we can "share culture in a world where everything has a license".

Related culture360.org article: Media Piracy in India

Related video: What do you think of media piracy?

Photo credit: flickr.com/photos/joi