The film director and his rights

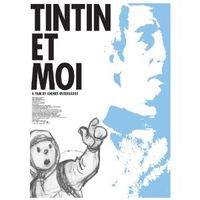

Interview with Henri Roanne-Rosenblatt by Gyora GAL GLUPCZYNSKI«Tintin and me» the documentary film of the Danish filmmaker ANDERS ØSTERGAARD's was nominated for the Nordic Film Prize at Goteborg.

GGG: Some elements of Ander's movie come from the movie, "Moi Tintin" you made in 1977. How did he proceed as far as buying the rights is concerned?

HRR: At the moment the Danish film was produced, I did not own the rights of my film any longer. Gérard Vallet and I had sold the rights to the Hergé Foundation a few years earlier (we were co-owners of the film)

In fact, we had first bought back the rights from our co-producer after the film came out. During the first years, the film was broadcast on several channels, ensuring us a varying income. When the film stopped being programmed, we had neither time nor money to find new distribution outlets for the movie. So when the Hergé Foundation contacted us to buy the rights, we did not hesitate. It seemed to us the best opportunity to keep the ball rolling. Indeed, the film could be permanently shown in the Future Tintin Museum, which should open as from 2007 in Belgium (Louvain-la-Neuve) . So, when Anders started his film, he had to deal with the Foundation only.

GGG: When there are two authors working on a common project, it probably implies a definite work split, as well as a corresponding rights sharing out. How did you manage to achieve it?

HRR: Gérard and I had been working together in radio broadcastings for a long time. We had already a great number of productions in common behind us. Regarding rights sharing out, there were absolutely no papers between us. We would only draw up a contract when we had to work with a third person. Between us, we would share out the rights as per the actual quantity of work and the personal commitment in the projects. Hence, it was not always a 50/50 allotment. As far as Tintin is concerned for instance, I was the one who first started to work on the project: first synopsis, topic research, collection of archives etc. Gérard joined later for the animation stand, the shooting and the postproduction. On "China", a film we made in 1971, he on the contrary started to work on the project earlier and, as a sequel, he had greater share of the rights.

GGG: What about Hergé?

HRR: Hergé's attitude may seem unbelievable in this respect, considering the international fame of his character: he allowed me a total freedom of action. He even never tried to read the script before the film came out. When I would ask him if he wanted to have a look on the first draft, he would reply: "It is your movie. I do not see why I should interfere in the making of it". It all started with an informal chat. We had a very positive exchange of opinions and that's probably why he decided to let me make the film. The encounter was quite straightforward: he knew who I was, he knew about my origins and my political opinions. We were not on the same board, to put it straight.

When I asked him how came no film had ever been made on him, he replied: "What about you doing it? I'm ready to put all my personal archives to your disposal". He then wrote a letter in which he authorized Gerard and me to use all his archives and all the images of his albums. It is amazing that a man with such a fame took the risk to unveil himself or even to put his reputation at stake. Extreme right media even launched a polemic at the time, since they could not conceive how Henri Roanne, "the so called leftist" could introduce Hergé, "the so called fascist". This man taught me a lot and probably wiped off what was left in me of black and white vision of politics.

GGG: What should a young filmmaker be aware of before making a film on a contemporary author?

HRR: First, one has a great freedom of criticism, which seems easier as long as one does not need images. As far as TINTIN is concerned, every single image contained in the albums is protected by a copyright that belongs either to the Hergé Foudation, or to the Moulinsart Foundation. (commercial and ethic rights are each managed by a distinct Foudation, which enables Hergé's heirs to intervene on different matters). It goes without saying that, if the rightful owners are not concerned by the polemical aspects of art, it soon proves impossible to make a film.

Second, we must underline the following as far as rights cession is concerned: too many young authors do not value properly their actual contribution to a production. They must bear this in mind whenever they make developments, i.e., synopsis writing, preliminary research, looking for travel expenses, telecommunications, time devoted to that work etc. If they don't, the situation often shows as follows at the end of the day: the original author holds no rights and they completely go to the co-producers!

Related publication:

FILM COPYRIGHT IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

This book is intended for practitioners, academics and students. The developments on contracts and moral rights will be of particular interest to lawyers outside continental Europe.

Pascal Kamina

Cambridge Studies in Intellectual Property

ISBN: 052177053X

Binding: Hardback

Pages: 460

© Cambridge University Press 2002

Similar content

By Kerrine Goh

29 Mar 2004

By Kerrine Goh

30 Nov 2011

By Kerrine Goh

12 Feb 2012

posted on

19 Aug 2013

posted on

19 Aug 2013