Challenges in accessing opportunities for visual artists in Southeast Asia: a comparison between Vietnam and the Philippines

Contributed by Lian Ladia, curator and co-founder of Planting Rice

Contributed by Lian Ladia, curator and co-founder of Planting Rice[caption id="attachment_57484" align="aligncenter" width="620"]

Open Studio at artist Vo Tran Chau’s studio, San Art Laboratory residency program[/caption]

Open Studio at artist Vo Tran Chau’s studio, San Art Laboratory residency program[/caption]For this article, Arlette Tran, curator of San Art in Saigon, one of the most active artistic platforms in Southeast Asia and Viet Le, an artist/curator and scholar were interviewed with regards to cultural mobility sources and access to information in Vietnam. Both were deeply concerned with how artists are empowered with available resources and how artists/curators and scholars mobilise in the constructs of urgency. Within each case, Planting Rice assessed comparisons with the climate of artists’ mobility and access to information in Manila, Philippines.

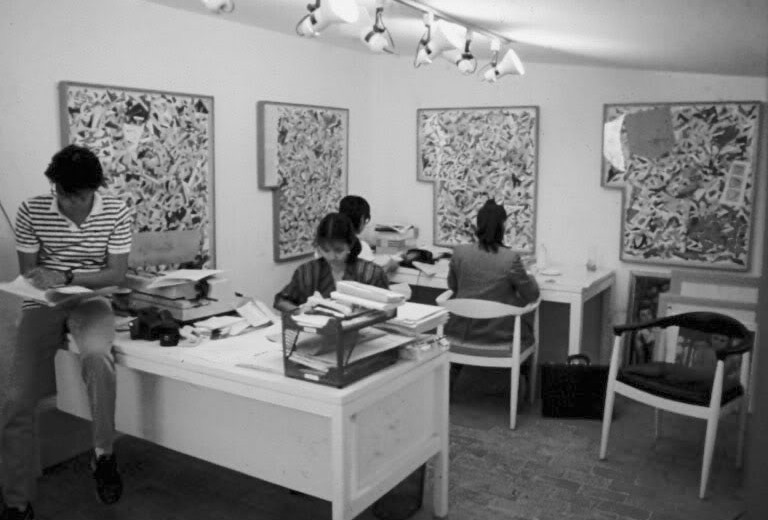

[caption id="attachment_57485" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

Nilo Ilarde and the staff of Pinaglabanan Galleries in their office, October 1984. On the walls are several of Roberto Chabet's China Collages[/caption]

Nilo Ilarde and the staff of Pinaglabanan Galleries in their office, October 1984. On the walls are several of Roberto Chabet's China Collages[/caption]Arlette Tran acknowledges that the government plays very little role in supporting the development of contemporary art in Southeast Asia in general (with the exception of Singapore). She mentions that the infrastructure of the art economy is still developing, growing and actually blooming in a robust way, its speed and urgency leave many spaces to develop innovative and even risky experiments. She mentions an example in Vietnam where a group of painters from Hanoi have organised an art fair in a department store in order to raise popular awareness to contemporary art – each booth was divided by a registered artist, and not a gallery. The event turned out into a big hit where visitor numbers and the quantity of sold artworks where in successful levels. While the democratic and originality of the concept of booths run by artists were different from the conventional formats of booths in more traditional art fairs, the level of quality of the event in itself requires to be further deliberated in compromising form with content.

Manila, with the similarity of detachment in terms of cultural mobility support by the government towards artists and cultural professionals, also has exhibitions (albeit considered serious) in the realm of private gallery owners may it be in shopping malls or the prime business district. For instance in a parking garage in a major shopping mall in the major financial district, art collectors and philanthropists have also been trying to create a yearly art fair called Art Fair Philippines. Within the guise of transforming the parking garage with what seems to be an international Southeast Asian art fair, Bloomberg Business online made an article with headline “Manila Garage Art Fair draws ‘Miss Saigon’, billionaires,” where major players in finance, come into transaction with players of the seemingly modest event. Yet the Philippine art world and contemporary artists take this seriously, for there are very few platforms where contemporary art is supported and marketed in the international realm of the local in the guise of a progressive yet parochial art community – there are few opportunities for critical exchange with the so-called international sphere. So even if the fair houses the auction house “Christies” in the same event, people still flock to go and support where there are no other avenues to all come together in an acknowledged platform.

Artist, writer and curator Viet Le who has written critical and scholarly works on Visual Studies in Vietnam and Southeast Asia and is currently a professor in Visual Studies at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco, was also interviewed with regards to how artists abroad access information in the region and its improvements. He mentioned that although there is certainly a level of difficulty getting information while abroad, access is still possible. He views the problem of centralisation, where some databases are probably needed. Presently the information can be tapped through networks and art spaces;he mentioned the Saigon contemporary art platform San Art or through Nha San collective, the first and longest artist run space for experimental art in Hanoi, or the Post-Vidai collection through commercial gallery Galerie Quyn. In terms of collaborations and partnerships with European organisations on digitisation of knowledge, practices and resources, he mentions that knowledge dissemination, practice and resources are often tied to arts or exhibition projects. Occasionally there are collaborations with funding bodies such as the Goethe Institut (Hanoi Doclab), British Council, L’espace (French embassy). On the Asian side, Asia Art Archive has recently worked with Nora Taylor on the digitisation of Hanoi Artist Vu Dan Tan and the archive of his home/studio/meeting space, Salon Natasha. Prince Claus Foundation has given support across a range of projects in Southeast Asia and Asialink Arts (Australia) has provided funding for art projects in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia. The Sylt Foundation funds artists’ residencies and has a South-South dialogue residencies, and Asian Cultural Council (ACC) fund research/art projects, as well as Creative Capital (New York), but these are mainly focused on individual artist/researcher projects rather than institutional knowledge building.

Within the context of Manila, Philippines, information is available and similarly not centralised. Domains of similar identities also form a swarm that can predict repositories of support. Indeed no national government projects fund digitalisation projects for cultural data preservation in the contemporary arts. However, it is the independent artists and researchers who form connections supported by international institutions like the Asia Art Archive (Artist/curator Ringo Bunoan’s research of seminal conceptual artist, Roberto Chabet), Prince Claus Foundation (support grants in the formidable years of the longest artist-run space Green Papaya Art Projects), Asian Cultural Council (research projects of curators like Roberto Chabet, Patrick Flores or Rod Paras Perez), Goethe Institut (support grants for experimental film workshop in the formidable years of experimental cinema in the Philippines), Asialink (residency funds for Asia-Pacific artist/curator exchanges in Manila), Alliance Française de Manille (residency programmes for Asia-Europe exchanges) and Japan Foundation (curatorship training workshops, artist exhibition funds and residencies in Japan, Southeast Asian collaborative exhibitions).

To centralise the case of contemporary art in the Philippines, one begins with key people: Purita Kalaw Ledesma (Founder of the Art Association of the Philippines, who produced books and exhibitions nationally and regionally, She also sponsored key figures and artists to study internationally in Europe and North America), Arturo Luz (Artist and founder of the Luz Gallery), Fernando Zobel (Artist and donor of the Ateneo Art Archives, Ayala Museum, Museo de Arte Abstracto Espanol in Cuenca, Spain), Roberto Chabet (via the research project and archive of Ringo Bunoan with Asia Art Archive), Raymundo Albano (via the Cultural Center of the Philippines archives), Agnes Arellano (artist and owner of artist-run gallery Pinaglabanan, with its own publication) and artist run spaces Big Sky Mind, Surrounded By Water, Future Prospects, Green Papaya Art Projects and the more recent 98B Collaboratory. If these archives were digitised and centralised, we could follow the history of contemporary and experimental art practices in Manila, Philippines.

In the case of curators and exhibition projects, the generative mode of producing an infrastructure, rather than expounding on topics/or theory have been popular in recent practices. For example, the contemporary exhibition and archive of Dutchman Hans van Dijk whose exhibition outlines the pre-boom of Chinese Contemporary art and experimental practices in Witte de With Rotterdam, The Chabet year-long exhibition with a recent book publication documenting ephemeral experimental conceptual practices in the 70’s and its influence on contemporary players in Manila, The collaboration of Stephanie Syjuco and the Reading Room Bangkok in a generative swap text exchange of historical and critical political and contemporary text by the Japan Foundation, and more recently discursive and research output projects happening in the Indonesian Visual Art Archive, Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, Thai Art Archives and The Singapore Art Archive project and exhibition of the National Gallery Singapore.

International institutions and artists (as opposed to local national art infrastructures) are the main independent singular references to motivate experimental work within the discussion of the contemporary arts. Unfortunately, artist-run motivated projects are mostly ephemeral in nature and decentralised. Perhaps in order for this to create strong rooted footholds, further investigative legwork and public support by localized and national cultural bodies should be required. The question is how can artist-communities locally and internationally come together to make this collaborative meeting happen.

Useful links:

- San Art in Saigon http://san-art.org

- Nha San Studio and collective http://www.syltfoundation.com

- Post-Vidai https://www.facebook.com/Post-Vidai-440787272730618/

- Goethe Institut Vietnam http://www.goethe.de/ins/vn/en/han.html

- Hanoi doclab http://www.hanoidoclab.org/en/

- British Council, Vietnam http://www.britishcouncil.vn/en

- L’espace, Vietnam http://www.institutfrancais-vietnam.com/vi/category/ha-noi/

- Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong http://www.aaa.org.hk

- Salon Natasha http://www.aaa.org.hk/Programme/Details/294

- Prince Claus Fund, The Netherlands http://www.princeclausfund.org

- Asialink, Australia http://asialink.unimelb.edu.au

- The Sylt Foundation http://www.syltfoundation.com/Latest-news/

- Asian Cultural Council http://www.asianculturalcouncil.org

- Roberto Chabet Archives http://www.aaa.org.hk/Collection/SpecialCollections/Details/4

- Hans Van Dijk Archives http://www.wdw.nl/event/dai-hanzhi-5000-artists/

- Goethe Institut Philippines https://www.goethe.de/ins/ph/en/index.html

- Alliance Francaise de Manille http://www.alliance.ph

- Japan Foundation, Philippines http://www.jfmo.org.ph

- Cultural Center of the Philippines, Manila http://culturalcenter.gov.ph

- The Reading Room Bangkok http://readingroombkk.org

- Thai Art Archives http://www.thaiartarchives.mono.net

- The Indonesian Visual Art Archive http://ivaa-online.org

- Myanmar Art Resource Center and Archive http://myanmarca.org

- The Singapore Art Archive https://www.nationalgallery.sg/about/news/press-room/acc-announcement