Reinterpreting Museum Objects through Rituals: Stories from Yogyakarta and Surakarta

As part of ASEF’s Call for Articles: Latest Trends in the Museum Sector in Asia and Europe, Dwirahmi Suryandari's article seeks to explore the rituals and tradition around objects and collections in some museums in Indonesia and see how this practice can provide a good approach to decolonize museum practice in the country and even abroad.

Many museums in Indonesia today are colonial legacy. And we are not just talking about the building or the collection but also about the management, the approach of displaying, and assessing the significance of the objects. Some of them, like National Museum in Jakarta holds collections inherited from Batavia Society and also not long ago, they became the custodian of 1500 object returned from Nusantara Museum in Delft. These objects have traveled so far back and forth and has undergone changes in their meaning. Even though they are now kept in the custodian of a museum in the home country, these objects are still distant from their original owner, which is the local community where they came from. However, in other museums like Museum Kereta Kraton (Royal Carriege Museum) in Yogyakarta and Radya Pustaka Museum in Surakarta rituals are still practiced around the collections and it shows how social and spiritual values of the objects are present. In this regard, these institutions are far from the western concept of a museum -where the purpose of objects are just for display, observation, and preservation. Both Museum Kereta Kraton and Radya Pustaka show the possibility of decolonizing museum practice in Indonesia by giving the corresponding community a chance to be engaged with the objects of their interest. This article seeks to explore the rituals and tradition around objects and collections in some museums in Indonesia and see how this practice can a good approach to decolonize museum practice in the country and even abroad.

Offerings at the ritual for Canthik Kyai Rajamala at Radya Pustaka Museum

Photo courtesy of Radya Pustaka Museum

Introduction: Shifting Away from Colonial Legacy

Museums all over the world face challenges to decolonize their day-to-day practice, from curatorial work such as assessing the objects, designing exhibition and interpretation, also how they interact with the public. After all, museum is indeed a colonial construct and a new narrative should be encouraged to speak for the underrepresented communities and untold stories. While the spotlight is mostly directed to museums in European countries where topics such as access to collection and repatriation are rising, many institutions in the post-colonial nations are also demanded to be more critical towards their approach.

Many prominent museums in these nations, including in Indonesia, are the legacy of colonialism. They were set up as research institute to support colonial system and as these nations became independent, many of them transformed into state owned museums and serve a new agenda. Most of these museums still approach their collection through colonial lenses, where objects are treated as mere artifacts. In independent nation-state like Indonesia, the interpretation and management of the objects are put in the frame of national identity, where collective memory is shaped and controlled.

Most of the of the time objects and their meanings are taken away from their original context. The display of regalia from dispersed kingdoms and dynasty gives the impression of conquer and control. Objects has lost their meanings and connection with the original owners or community. Many have criticized this phenomenon as a continuation of coloniality in museum practice, where the value of objects is determined by a group of people who are not culturally or historically related to them. As Arjun Appadurai in the introduction of The Social Life of Things (2014) mentioned that major art and archaeology collections are of “Western taste for the past and for the others”. Therefore, it only makes sense that inclusivity should become a priority in the process of decolonizing museum.

Kanjeng Nyai Jimat being prepared for Jamasan at the Royal Carriage Museum of Yogyakarta

Photo courtesy of www.kratonjogja.id

Performing Rituals in Museums

An interesting practice took place in Museum Radya Pustaka, in Surakarta, Central Java where a particular object, which is called Canthik Kyai Rajamala is kept. Canthik is a Javanese word for figure placed at the front of a traditional boat. This particular object was made under the commissioning of Pakubuwana IV from the year 1811 and has been stored in the museum for more than a hundred years.

Kyai Rajamala is still very close to the heart of many. One of them is a local organization called Dharma Bakti Budaya who regularly conduct a ritual for this object on the eve of a Friday Kliwon -a sacred day in Javanese calendar- as a form of respect and devotion. In a recent interview, Abisa, a member of this organization, described the ritual and the purpose of this activity, “We have done this since many years ago. We want to honor Kyai Rajamala, as he is our ancestor.” He also said that the ritual is performed to get the blessing from the Kyai and bad luck will occur otherwise.

This is an example how museum in post-colonial nation like Indonesia functions as an institution that host a living tradition instead of just being a cabinet of curiosity with dead artefacts. The community has the opportunity not only to access the objects but also to give different interpretation. Thus, making the object has a social and spiritual significance.

Another museum is Museum Kereta Kraton (Royal Carriage Museum), part of Yogyakarta Royal Palace. A ritual is performed every Tuesday Kliwon in the Sura month according to Javanese calendar. The ritual is called Jamasan, means cleansing in Javanese. The ritual begins with prayers and placing of offerings. Afterwards, two carriages are brought out of the museum. A group of royal courtiers devoted to the royal family called Wahana Sarta Kriya then bathe these carriages with water, lime juice, and flowers. The Jamasan is performed for particularly for Kanjeng Nyai Jimat, a name of a carriage once used by the first king of Yogyakarta, Prince Mangkubumi and one other escort carriage. The royal palace considers this carriage as a sacred heirloom. People usually gather in the courtyard of the museum to watch and collect the water that drips down from the body of the carriage. They believe that this water is potent thus they will use it to water their plants or just keep a bottle at home for good fortune.

Ritual could be seen as a means to assert power. It could be used as a way to maintain the significance of the ruling authority or a cultural group. As confirmed by Fajar Widjanarko, a young curator of the Yogyakarta Royal Palace collection and a culture enthusiast, that rituals are “Indeed held for the legitimation of the ruling authority. However, in the context of museum practice, rituals can be a way to contextualize old narrative for the present day”.

Interestingly, these rituals at both museums happen as part of local belief and traditions, instead of the framework of decolonization. This proves that putting back objects and collections into their social and spiritual context is possible because people are still connected to these objects and in fact there are still many more cultural practices associated with objects and collections at Indonesian museums.

Members of Dharma Budaya Lestari performing rituals for Canthik Kyai Rajamala

Photo courtesy of Radya Pustaka Museum

Reconnecting with the community

In the light of decolonization, museum and its curators should embrace the possibility of involving more people with interest and knowledge of the object and collection. Consultation should occur in various level of museum work, from research to exhibition design. The original owner or interest group should have more to say in the interpretation of the objects.

Rituals and other direct interaction with objects might not be suitable for every museum. However, what important is opening up access and possibilities for the community to engage with objects of their interest. This approach will enable museum and the community to produce a new meaning for things that used to be kept away from them.

Cover image: Offerings at the ritual for Canthik Kyai Rajamala at Radya Pustaka Museum

Photo courtesy of Radya Pustaka Museum

About the Author:

Dwirahmi Suryandari holds a Masters in World Heritage Studies from Brandenburg University of Technology, Germany. Over the last 10 years she has been involved in a number of projects relating to urban heritage, World Heritage nominations, and museum exhibitions. She is now working at Southeast Asia Museum Services (SEAMS) as museum and heritage specialist.

Similar content

posted on

30 Nov 2011

posted on

03 Feb 2012

from - to

21 Apr 2012 - 04 Nov 2012

posted on

29 Oct 2015

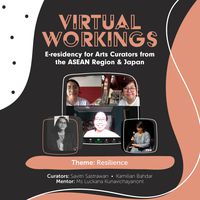

By Kamiliah Bahdar and Savitri Sastrawan

15 Mar 2021