An introduction to Australian cultural policy

Australia became a nation in 1901 with the federation of six British colonies into a single ‘Commonwealth of Australia’. Seven years later the new nation launched into cultural policy by creating the Commonwealth Literary Fund. But it was not until 1975 that the real foundation of modern Australian cultural policy was laid with the establishment of the Australia Council for the Arts. Government chose an ‘arm’s length’ British-style model for the Council, rather than a ministry or department of culture, over fears of political interference in arts support.

Australia became a nation in 1901 with the federation of six British colonies into a single ‘Commonwealth of Australia’. Seven years later the new nation launched into cultural policy by creating the Commonwealth Literary Fund. But it was not until 1975 that the real foundation of modern Australian cultural policy was laid with the establishment of the Australia Council for the Arts. Government chose an ‘arm’s length’ British-style model for the Council, rather than a ministry or department of culture, over fears of political interference in arts support.The Australia Council brought a new energy to Australian cultural policy. It also brought into sharp focus the government’s jumbled approach to cultural policy, with culture programs and policies scattered across government departments and agencies. In 1984 these scattered cultural interests were consolidated into the Department of Arts, Heritage and Environment. Despite minor reshuffling, this departmental model remained in place until 2011, when responsibility for culture was split between the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (arts and moveable heritage) and the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (non-moveable heritage).

Although strongly identified with a British ‘patron’ model, Australia’s national cultural policy system is best described as ‘mixed’: it uses a mixture of arm’s length peer-reviewed funding, direct funding by departments and ministers funding, and state ownership.

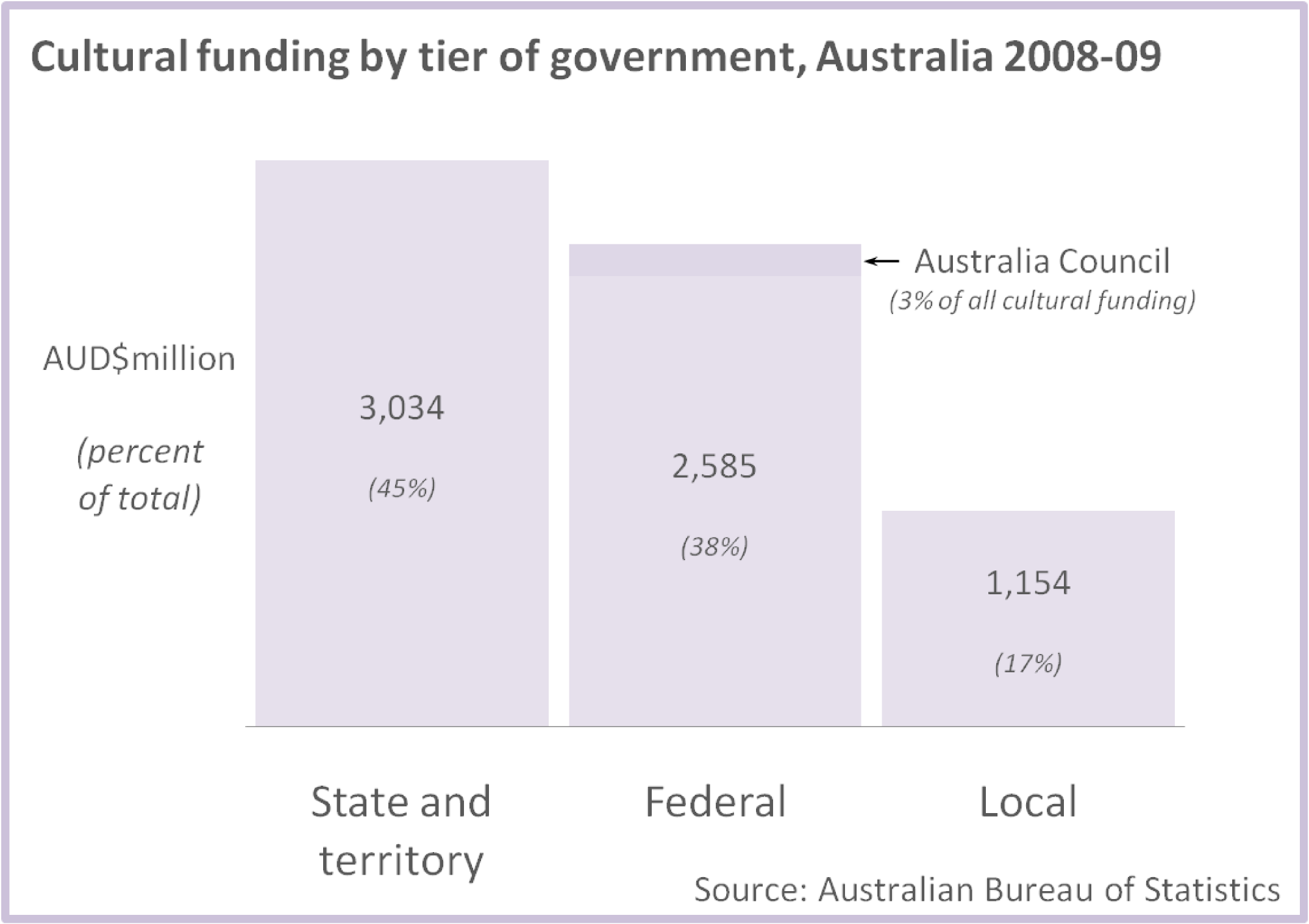

But national federal government is not the only player in Australian cultural policy. The country has three tiers of government: federal; state and territory; and local. Cultural policy at the state and territory level tends to be coordinated by government departments and ministries, which, as the figure below shows, oversee the greatest portion of the country’s cultural funding.

The different government tiers also spend on different things. In 2008-09, more than half (53 percent) of federal cultural funding went to broadcasting; most of this going to two state-funded, though not state-controlled, broadcasters (the Australian Broadcasting Commission and multicultural programmer the Special Broadcasting Service). State and territory governments, on the other hand, provided the majority (74 percent) of funding to Australian heritage, and spent two and a half times more on cultural infrastructure than federal government.

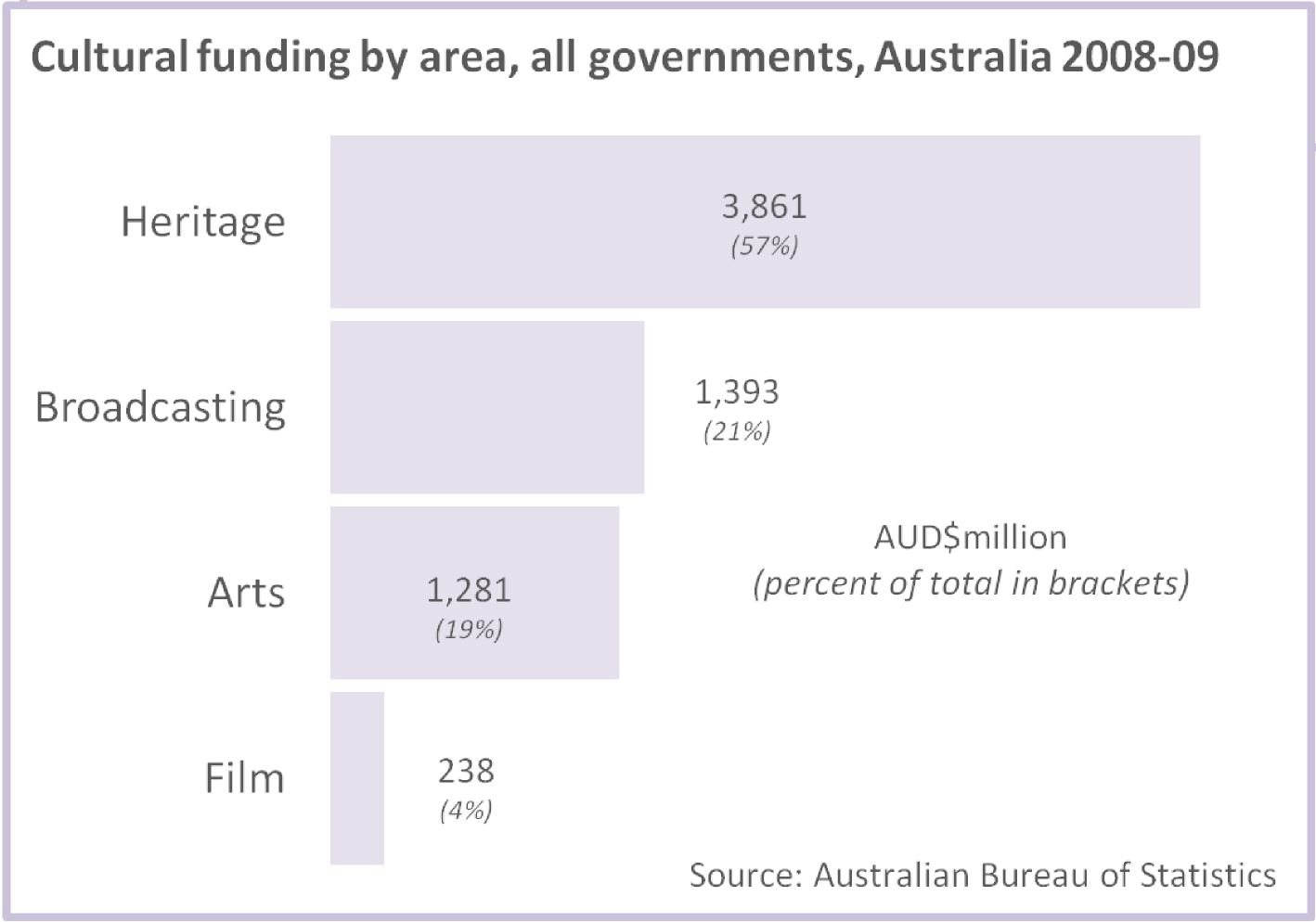

The figure below shows funding by all three tiers of Australian governments across key cultural domains.

The rest of this article will focus on federal cultural policy only.

Australian federal governments have tended to adopt a reactive and piecemeal approach to cultural policy. Typical of this approach are the years of the coalition government of John Howard from 1997 to 2007. In these ‘Howard years’, cultural policy was developed through a series of stand-alone reviews, including reviews of support for major performing arts companies and the visual arts sector. (Detailed in Re-visioning arts and cultural policy). Although they brought increased funding, the reviews were not part of a coordinated transparent long-term cultural strategy – they were discrete, stand-alone, or ‘piecemeal’.

Creative Nation is the obvious exception to Australia’s piecemeal cultural policymaking. Launched in 1994 by the Labor government of Paul Keating, Creative Nation was the first time an Australian federal government had outlined a ‘grand plan’ for culture. It brought unprecedented levels of organisation and interest to Australian cultural policy.

A change in government in 1996 cut short Creative Nation’s vision, but the policy’s memory lingered. In the early 2000s, with the reviews of the Howard years in full swing, debate re-emerged about whether Australia should again have a national cultural policy. The debate gained traction at a 2005 forum that led to an essay Does Australia need a cultural policy? by prominent cultural economist David Throsby, and a book that arose from the forum. A robust case was mounted an explicit cultural policy would bring coherence and transparency to Australia’s cultural policies.

By 2008 the platform was set for strong consensus at the 2020 summit, a grand planning meeting convened by Kevin Rudd’s newly elected Labor government. Participants in the Summit’s ‘creative stream’ advocated three main things Australian cultural policy needed:

- A national cultural and design strategy and policy.

- A dedicated ministry of culture (rather than an arts division within a wider department).

- A ‘whole of government’ approach to culture.

Rudd’s Minister for the Arts, ex-rocker Peter Garrett, began working on a national cultural policy, but progress was interrupted with a change in Minister in 2010. The new Minister has pledged to continue developing the policy, though no progress is evident at the time of writing.

In the meantime, Australian cultural policymakers are working on issues familiar to policymakers everywhere: the impact of technology on culture; how to encourage greater private philanthropy and corporate sponsorship; how to promote sustainable cultural organisations and artists’ careers; how to encourage broader cultural engagement; the linkages between the arts and the creative industries; and the balance between ‘heritage arts’ and newer art forms. Given the country’s large geographical size, regional infrastructure and access are also high on the Australian cultural policy agenda. Australian researchers are also at the forefront of efforts to measure ‘intrinsic’ artistic quality or artistic ‘vibrancy’.

Perhaps more telling, however, are the issues absent from recent policy developments and debate.

Australian cultural policy has tended to shy away from ‘big picture’ issues, such as rights, values and ethics, and has tended to avoid broader notions of culture. Rather, cultural policies have focused on the practical and palpable – on program delivery, jobs, and on the arts and heritage industries. This pragmatic and narrow focus has resulted in two main problems. First, indigenous Australian cultures do not hold as central a position in Australian policy as might be expected in light of their intrinsic uniqueness to Australia. An opportunity is thus missed for cultural policy to guide other policy domains and promote reconciliation (see Monolithic cultural policy).

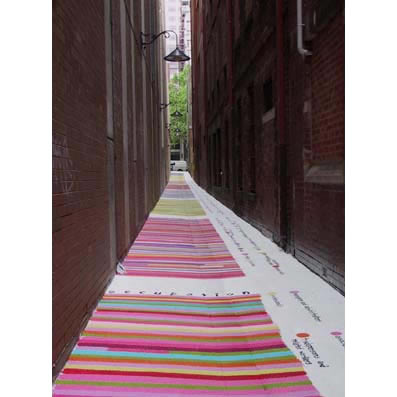

[caption id="attachment_12783" align="aligncenter" width="397" caption=""There are a few facts I think you ought to know" - work by Louisa Bufardeci"]

[/caption]

[/caption]Second, cultural policy has not engaged well with policy debates based on broader notions of culture. For example, cultural policy was outmanoeuvred in the ‘culture wars’ of the Howard years, when the Prime Minister and his deputy went on an offensive against multiculturalism and challenged migrants to assimilate to ‘Anglo-Saxon’ values. The move struck a blow to decades of multicultural policymaking and sparked a tide of parochialism that culminated in the Cronulla riots of 2005. The new government has set about rebuilding multiculturalism, though, tellingly, not through its core cultural policy agencies.

Also missing in Australian cultural policy is debate over the erosion of the arm’s length principle. Growing political interest in culture and the creative industries has seen government influence creeping into cultural policies. Between 2001 and 2009, for example, arm’s length funding through the Australian Council dropped from 26 to 18 percent of federal funding to the visual, performing and literature arts. In 2008-09, nearly two thirds (64 percent) of Australia Council funding was administered by the Council on behalf of the government – these are funds delivered by an arm’s length agency, but not decided on at arm’s length. The recent transfer of the arts portfolio to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet represents another potential shortening of the arm. Oddly, this fundamental shift in the philosophical underpinnings of Australian cultural policy has occurred largely without comment.

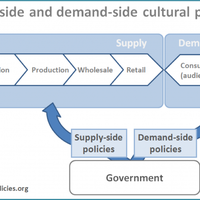

Part of the problem may be a poverty of inquiry in Australian cultural policy. Although Australia has an enviable amount of information and data on culture, this evidence base is not being well utilised for policy. For example, data showing phenomenal rises in creative arts participation in the Australian population has been largely ignored, despite the implications that this ‘creative revolution’ has for cultural policy. (In particular, the need for demand-side cultural policies to rebalance policy, which I will explore in an upcoming article) The recent disbanding of the Cultural Ministers Council, an intergovernmental committee that was a key producer of information on Australian cultural policy, represents another setback to the cultural policy research infrastructure.

So, in addition to the three consensus issues identified at the 2020 Summit, I would add four more:

- Indigenous culture needs to be given a more central place in Australian cultural policy.

- Broader concepts of culture need to be adopted in Australian cultural policy discourse.

- A debate needs to take place on the independence of government’s cultural support (or, more specifically, on how to ensure departments and arm’s length agencies are doing what they do best).

- There needs to be more analysis and interpretation of existing data on Australian culture.

- More demand-side cultural policies are needed to rebalance Australia’s predominantly supply-side policy mix.

Constantly in flux, passing between portfolios and ministers, and rarely featuring high on government agendas, cultural policy in Australia has been a constant battle with disorganisation and disinterest. But all that could change if the current government follows through on its commitment to develop a national cultural policy. We may be at a rare turning point in Australian cultural policy – a point as critical as the birth of cultural policy in 1908, the establishment of the Australia Council in 1975, and the release of Creative Nation in 1994.

Christopher Madden is a cultural policy research analyst and statistician. He has worked for a range of cultural policy agencies across Australasia. From 2001 to 2008 he was Research Analyst at the International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies. Christopher’s research can be viewed at his website artspolicies.org.

References and resources

History

Commonwealth arts policy and administration, Gardiner-Garden, 2009, Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia, Canberra.

Analyses

Re-visioning arts and cultural policy: Current impasses and future directions, Craik, 2007, ANU E Press and Australia and New Zealand School of Government.

Making meaning, making money: Directions for the arts and cultural industries in the creative age, Oakley and Anderson eds., 2008, Cambridge Scholars Press, Cambridge.

Australasian edition Cultural Trends:

Part 1, volume 19 number 4, 2010

Part 2, volume 20 number 1, 2011

Research resources

Australia Council research hub

National Centre for Culture and Recreation Statistics, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Cultural data online

Screen Australia research

Institutions

Arts and culture: Office for the Arts, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Heritage: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

Broadcasting: Australian Communications and Media Authority

Film: Screen Australia

Others (including state and territory offices): Australia, the IFACCA directory

News and publications

Australian policy online Creative & Digital

IFACCA resources, Australia

Similar content

posted on

14 May 2015

posted on

19 Aug 2013

12 Jul 2011