19 Aug 2016

The art of archiving lost things | From Monet to Tracey Emin

What do Tracey Emin and Claude Monet have in common? Both created works that vanished into thin air and consequently are now part of galleries archiving lost art. Lai DEL ROSARIO explores what it means to archive objects that are no longer there.

The archive is an idea often overlooked or taken for granted. The imagery of a dark, dusty room and mounds of old-smelling documents does nothing to convince the non-researcher of its relevance in contemporary society. In fact, discussions surrounding the existence of archives in the course of recent history have been surprisingly contentious. Derrida, Foucault, and contemporary art curator Okwui Enwezor have all dabbled and theorized on them. The practice of archiving, along with developments in technology, is constantly evolving and adapting more dynamic means of keeping and organising objects and data.

What constitutes an archive? Common definition describes it as a place where records, often unpublished with cultural or historical value, are stored. They serve as primary source documents and are unique, unlike books and magazines (kept by libraries). Films, photographs, written letters, and artworks can make up archival collections. Some are open to the public while others are less accessible for reasons of conservation or sensitivity of information.

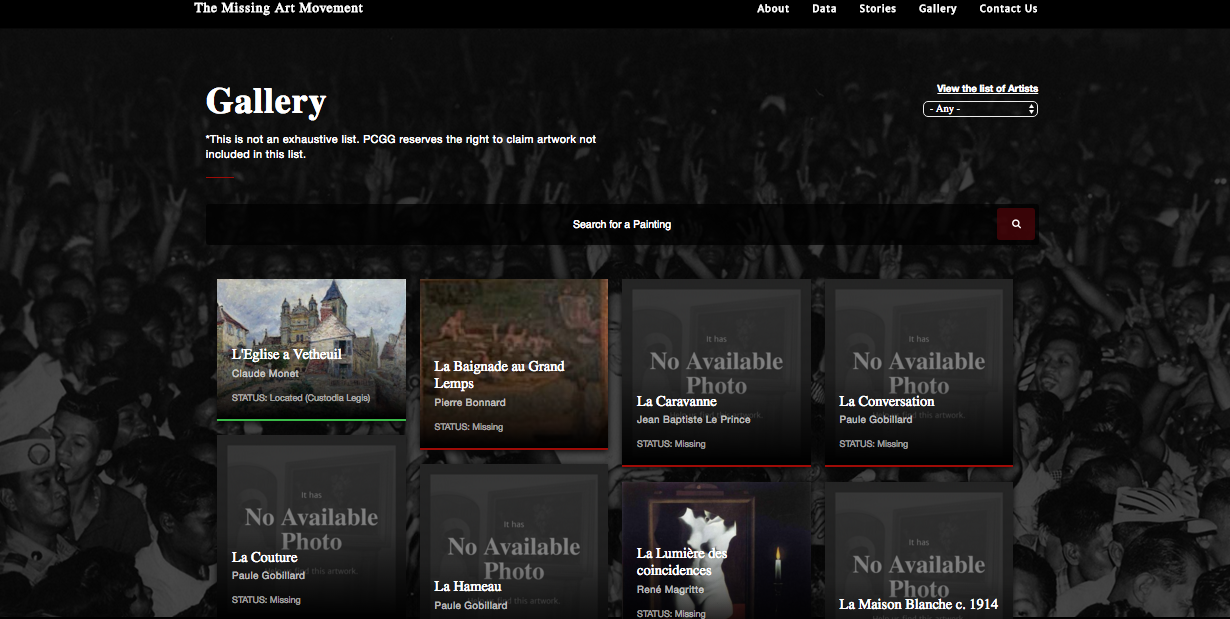

In an attempt to further expand perspectives and uses of archives in the art world, this article focuses on two web-based examples - the Gallery of Lost Art project by the Tate Modern, and the Missing Art Movement by the Philippine Commission on Good Governance. Both have specific agendas - the former intends to identify the impact of lost objects in art history, while the latter aims to recover artworks for socio-political and economic reasons.

The Gallery of Lost Art

The Gallery of Lost Art was an interactive virtual exhibition that ran for a year in 2013 and now exists as a digital archive and documentation of the exhibition. It focused on over 40 important artworks from the last 10 years that have, either, expired (such as performances), gone missing, been destroyed or discarded. Images, essays and films about the works were also included in the exhibition. Pieces by Marcel Duchamps, Pablo Picasso, Tracey Emin, Willem De Kooning and more, were featured. Curator Jennifer Mundy explains, “Art history tends to be the history of what has survived. But loss has shaped our sense of art’s history in ways that we are often not aware of.”

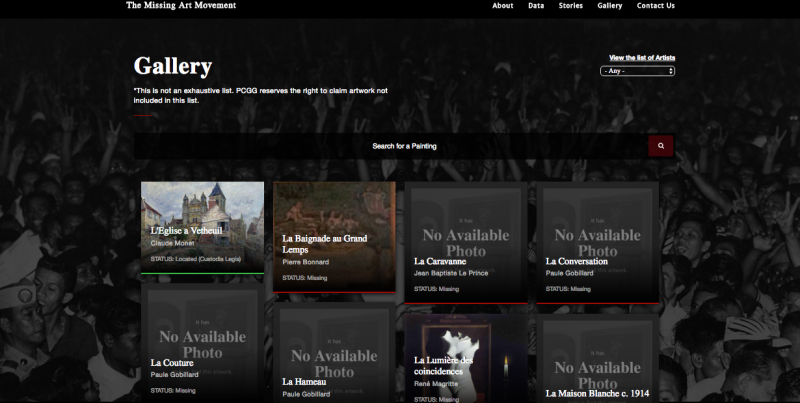

[caption id="attachment_60238" align="aligncenter" width="400"]

Wanted poster (2001), Lucian Freud. Courtesy Tate Gallery[/caption]

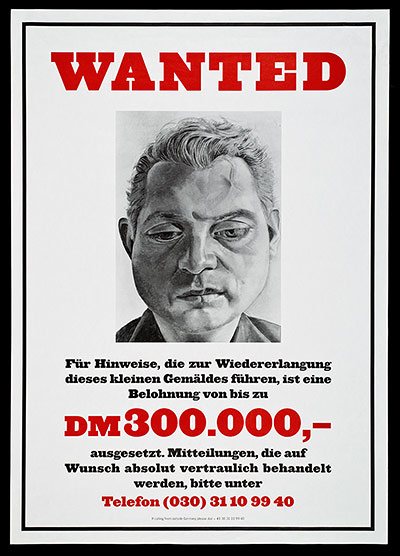

Wanted poster (2001), Lucian Freud. Courtesy Tate Gallery[/caption]A Francis Bacon portrait by friend and artist Lucian Freud, for instance, was yanked from the Neue National Gallery in Berlin in 1988. Thirteen years later in 2001, Freud was still in search of the work, going as far as to create a ‘wanted’ poster for the painting and offering a substantial reward for it. Tracey Emin’s tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-95 (1995) was destroyed in a fire at the Saatchi warehouse in East London in 2004.

Some ways of being lost were less unexpected, such as Robert Rauschenberg’s “Erased de Kooning” (1953) for which the artist asked Willem de Kooning to draw an image that Rauschenberg would consequently ‘erase’ by rubbing out the image. Other cases of loss were self-initiated, such as John Baldessari’s “Cremation Project” (1970) in which the artist burned all his paintings between 1953-1966 and used the ashes as ingredients to make cookies.

[caption id="attachment_60242" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995), Tracey Emin. Copyright believed to be Jay Jopling/White Cube (London)[/caption]

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995), Tracey Emin. Copyright believed to be Jay Jopling/White Cube (London)[/caption]As The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones puts it, “vanished art has a habit of refusing to go away.” What is interesting about the Gallery of Lost Art is how it attempted to exhibit objects that were no longer there. In fact, without the corresponding documents, photos, and films, the works would have ceased to exist. It took advantage of digital technology to present a virtual exhibition that recreated artworks. The gallery also served as a kind of paradoxical archive, wherein what was displayed were traces of existence, not the actual works. It put value not only on tangible things but on their history and provenance.

Additionally, through interactive screens and collected essays, the gallery provided not just a space for presentation but a platform in which individuals could contribute their own reflections and initiate further discussions on what it means for something to be lost. It demonstrated what the incidence of loss can provoke artists and institutions to do even years after, such as Lucian Freud’s Wanted poster.

Today, the Gallery of Lost Art serves as an archive of archives. The virtual exhibition and its interactive features no longer exist, rather, the project has been documented as an internet ‘happening’ that once archived lost artworks some three years ago. Its contents remain accessible through the Tate, British Film Institute, and ISO Design websites, and a catalogue for sale.

The Missing Art Movement

The Missing Art Movement is an online archive created by the Presidential Commission on Good Governance (PCGG) in an attempt to recover lost artifacts from former Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos and his wife Imelda’s vast collection of art. The database is impressive to say the least, with artists ranging from Goya’s Portrait of the Marquesa de Santa Cruz and Picasso’s Reclining Woman VI.

PCGG believes that public funds were used to build Marcos’ private collection during his regime from 1965-1986 (with the latter half being ruled under martial law). After Marcos was removed from power in 1986 through a series of mass protests and demonstrations, he and his family hurriedly left for Hawaii where they stayed in exile until Marcos’ death in 1989. With their escape came the disappearance of a vast number of treasures, of which the art collection represents but a fraction.

Soon after Marcos’ flight, succeeding president Corazon Aquino established PCGG, a quasi-judicial agency mandated to recover ill-gotten wealth amassed during Marcos’ administration. It operates by recovering artworks and reselling them, effectively circulating public funds back to the government. Thirty years later, PCGG is still on the hunt and has created the Missing Art Movement, to celebrate its 30th anniversary.

The database of Marcos’ private collection was developed by piecing together art gallery receipts, shipment records left by the family, and other relevant sources. While the list is not exhaustive, a conservative estimate already values the collection at USD 300 million (EUR 270.6 million). The most expensive painting ever paid for, based on a 1983 receipt, is believed to be Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child bought for USD 3.5 million (EUR 3.16 million). The work is yet to be recovered.

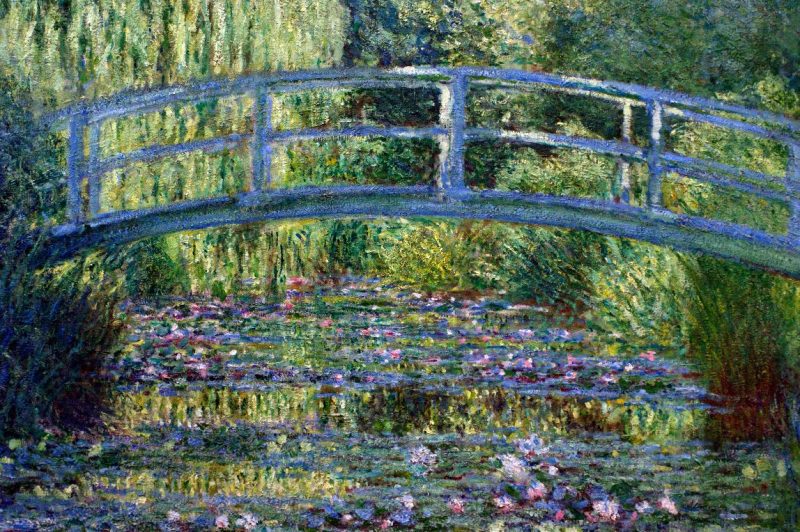

Some pieces were found in Metro Manila, while others were seized in places as far as France. A number had been peddled to unknowing individuals and was consequently put under litigation, such as Monet’s “Le Bassin aux Nympheas” (1899), which was bought by a British billionaire for USD 10 million (EUR 9 million) in New York, just in 2013. The rest is believed to still be in the possession of the Marcos family.

[caption id="attachment_60237" align="aligncenter" width="620"]

Le Bassin aux Nympheas (1899), Claude Monet. Courtesy The Missing Art Movement[/caption]

Le Bassin aux Nympheas (1899), Claude Monet. Courtesy The Missing Art Movement[/caption]As of August 2016, there are 283 listed works, from which 160 are still missing and 104 have been recovered and resold by the PCGG. Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s Adoration of the Magi (c. 1600) is one of those recovered and sold for USD 300,000 (EUR 271,000).

[caption id="attachment_60241" align="aligncenter" width="620"]

Adoration of the Magi (c. 1600), Pieter Brueghel the Younger[/caption]

Adoration of the Magi (c. 1600), Pieter Brueghel the Younger[/caption]The income generated from these sales has reached USD 17.34 million (EUR 15.64 million), a portion of which is said to be allotted as compensation to the "9,539 Filipinos, or their heirs, who were tortured, summarily executed or disappeared during Marcos’ rule between September 1972 and February 1986" (Doyo, M.C., 2013).

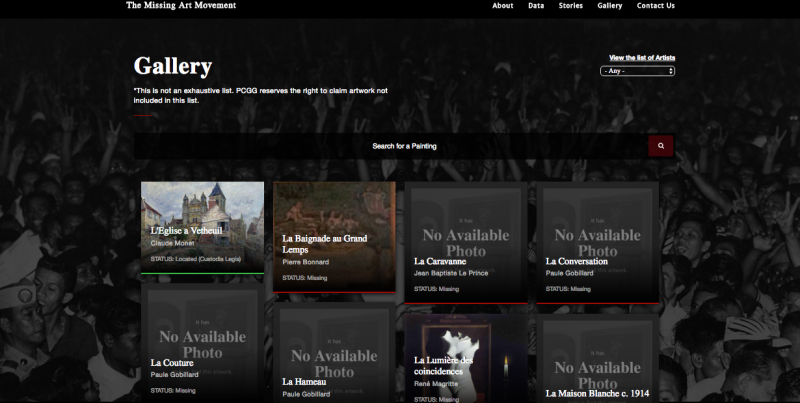

As a digital platform, the Missing Art archive functions as a tool for collaboration to encourage crowdsourcing for intelligence-gathering toward filling in the blanks of history and identifying other missing works. However, while users can leave comments for leads, it is still unknown whether the online database has actually led to any recovery since its launch.

The Missing Art Movement is also a modern-day example of how an archive influences national identity building. In this case, it tells the story of a country that suffered political abuse and how it is still trying to rebuild itself in the face of resistance and adversity. In essence, finding the lost artworks is not just a way for the PCGG to recover public funds; it is also a way of seeking justice for martial law victims. It stands as a reminder that the political debacle caused by Marcos has not ended. Its consequences are still being grappled with to this day.

[caption id="attachment_60240" align="aligncenter" width="620"]

Screenshot from The Missing Art Movement. Courtesy The Missing Art Movement. Last accessed 10 Aug 2016[/caption]

Screenshot from The Missing Art Movement. Courtesy The Missing Art Movement. Last accessed 10 Aug 2016[/caption]The Gallery of Lost Art and the Missing Art Movement raise questions as to the relevance, function, and make of archives today. They put into question the value of missing objects. Does the value of lost art end with its disappearance, or does it live on in the trail of its memory?

Digital technology has redefined an archive’s accessibility. Wherein before they were site-specific and required physical handling in order to use, this has been changed by the internet, making it easier for the public to access information. Digital representations of objects – images, videos, essays – allow researchers to discover and analyse them without physical interaction.

However, if data can so easily be gathered and added onto a digital platform, it could just as easily be deleted from a website’s server. Digital archives therefore risk becoming inconsistent and unreliable as compared to tangible ones, where de-accessioning would require a longer process and probably leave traces.

Nonetheless, both the Gallery of Lost Art and the Missing Art Movement are able to demonstrate how loss affects art history as well as a nation’s narrative, whether the cause of loss is conceptual, accidental or criminal. In this sense, archives have become dynamic tools for communication, offering multiple sources, angles and interactive possibilities that engage users beyond the physical handling of an object.

-

Further reading

http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_279207_en.pdf

http://uwf.edu/dearle/capstone/manoff.pdf|

http://inlivingmemory.eu/typology/artwork/

-

Lai del ROSARIO is an art manager and freelance writer with a keen interest in cross-cultural creative collaborations, having lived and worked in Switzerland, France, and the Philippines. She is also currently developing an online platform that promotes creative spaces in cities.

Similar content

posted on

30 Apr 2015

posted on

30 Jun 2016

posted on

06 Sep 2017

posted on

12 Feb 2012

posted on

29 Jun 2016

posted on

09 Feb 2017